DARPA Starts to Tackle Radar/Comm Sharing

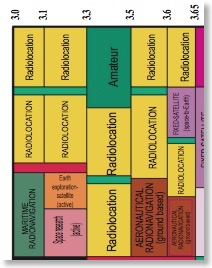

When sharing was proposed, the same IRAC was able to dictate sharing conditions to FCC with the functioning of the radar as originally designed being the paramount issue. Overprotection that limited private sector sharing was of little concern to IRAC and the technical criteria development was often shrouded in secrecy to protect the technical details of the radars involved. This is shown in the case of the 5 GHz U-NII sharing where we have the bizarre sharing conditions of § 15. 407:

According to these 2 sections if an unlicensed device detects any signal on the channel greater than - 64 dBm (non techies: that is less than a millionth of a milliwatt!) it must avoid using that channel for the next 30 minutes! Double checking to see if it is a false alarm due to noise is not allowed by this rule.

§ 15.407(h)(2) Radar Detection Function of Dynamic Frequency Selection (DFS)

A channel that has been flagged as containing a radar system, either by a channel availability check or in-service monitoring, is subject to a non-occupancy period of at least 30 minutes. The non-occupancy period starts at the time when the radar system is detected..Radar Detection Function of Dynamic Frequency Selection (DFS). U-NII devices operating in the 5.25-5.35 GHz and 5.47-5.725 GHz bands shall employ a DFS radar detection mechanism to detect the presence of radar systems and to avoid co-channel operation with radar systems. The minimum DFS detection threshold for devices with a maximum e.i.r.p. of 200 mW to 1 W is −64 dBm. For devices that operate with less than 200 mW e.i.r.p. the minimum detection threshold is −62 dBm. The detection threshold is the received power averaged over 1 microsecond referenced to a 0 dBi antenna. The DFS process shall be required to provide a uniform spreading of the loading over all the available channels…Non-occupancy Period.

A channel that has been flagged as containing a radar system, either by a channel availability check or in-service monitoring, is subject to a non-occupancy period of at least 30 minutes. The non-occupancy period starts at the time when the radar system is detected.

(It is ironic that the recurring interference to NOAA’s TWDR weather radars is not addressed here since TDWR is a doppler system unlike FAA radars. It appears that DoD and FAA dominated the secret IRAC deliberations on the criteria that was dictated to FCC by NTIA and did not pay much attention to NOAA’s radar technology.)

To NTIA’s credit they did choose radar/communications sharing as the theme of the 2011 International Symposium on Advanced Radio Technologies, their annual public technical conference in Boulder CO. The conference was entitled “Developing Forward Thinking Rules and Processes to Fully Exploit Spectrum Resources: An Evaluation of Radar Spectrum Use and Management”. In the proceedings, is a paper (p. 214) from your blogger entitled “Thoughts on Radar/Communications Spectrum Sharing”. This paper breaks from the static precedent of U-NII radar sharing and suggested time dynamic sharing, noting that while 1000 ms/s spectrum access was essential when circuit switched voice dominated mobile traffic, today’s packet switched data is the dominant traffic and packet switching technology can readily make reliable networks our of time intermittent links.

The paper was discussed at the conference and here are two comments from the proceedings:

A second idea that is very important, first advocated for by Michael Marcus, is about unlicensed low power uses and it has spawned a revolution of technological developments that take advantage of that possibility. -- Phil Weiser, U. Colorado (Formerly senior advisor for technology and innovation to the National Economic Council at the White House)

I also wanted to take just a minute to recognize that Mike Marcus, who was originally going to be on this panel but couldn’t make it in the end, also put together a paper that talks about some sophisticated techniques for sharing with radars. -- Julius Knapp, FCC

The purpose of this conference is to provide information on the SSPARC program; promote additional discussion on this topic; address questions from potential proposers; provide a forum for potential proposers to present their capabilities for teaming opportunities; and following the conference, conduct pre-scheduled one-on- one meetings with the Program Manager as described below.

PROGRAM OBJECTIVE AND DESCRIPTION: DARPA anticipates releasing the BAA for SSPARC with the objective described in this section. The objective of the SSPARC program is to improve radar and communications capabilities through spectrum sharing. SSPARC develops technology applicable to spectrum sharing between military radars and military communications systems, and between military radars and commercial communications systems. SSPARC includes work on spectrum sharing systems and separation mechanisms, supporting technologies that improve performance when sharing spectrum, theoretical performance limits and grounded design techniques, and relevant regulatory topics.

It is gratifying to see that this concept is moving along towards more detailed study after being ignored for a long time.

Now if only the cellular industry would address the topic of using intermittent access to radar spectrum fro CMRS with an open mind rather than insisting on an unrealistic goal of meeting all their spectrum demands solely by reallocation.

UPDATE

The DARPA BAA is now posted here. From the introduction:

The Shared Spectrum Access for Radar and Communications (SSPARC) program seeks to improve radar and communications capabilities through spectrum sharing.

Spectrum congestion is a growing problem. It increasingly limits operational capabilities due to the increasing deployment and bandwidth of wireless communications, the use of net-centric and unmanned systems, and the need for increased flexibility in radar and communications spectrum to improve performance and to overcome sophisticated countermeasures. Radar and communications jointly consume most of the highly desirable spectrum below 6 GHz. SSPARC seeks to develop sharing technology that enables sufficient spectrum access within this desirable range for radar and communications systems to accomplish their evolving missions.

The SSPARC program seeks to support two types of spectrum sharing.

- Spectrum sharing between military radars and military communications systems (“military/military sharing”) increases both capabilities simultaneously when operating in congested and contested spectral environments.

- Spectrum sharing between military radars and commercial communications systems (“military/commercial sharing”) preserves radar capability while meeting national and international needs for increased commercial communications spectrum, without incurring the high cost of relocating radars to new frequency bands.

UPDATE 2/26/13

Today’s public meeting on the DARPA BAA was a great success with about 150 people present! There clearly is great interest in the topic in the R&D community.

Is there any interest in using such spectrum from the cellular establishment or will they continue their negative reaction to the PCAST report and demand 500 MHz of new spectrum subject to

- nationwide availability

- 24/7 1000 ms/s availability

- compliance with 3GPP band plans?

But as the PCAST report points out this is an unrealistic goal in a country with the largest most information intense military in the world. The cellular industry aimed too high in the “booster amplifier” rulemaking, Docket 10-4. Should they be more reasonable here?

UPDATE 3/15/13

The SSPARC program now has the logo shown at left. It carefully does not show any physical system in order to be open minded about possible designed. DARPA has now posted on their website presentation from the Proposer’s Day. Of particular interest is a presentation from DoD spectrum managers showing how much spectrum is used by radar today.

The SSPARC program now has the logo shown at left. It carefully does not show any physical system in order to be open minded about possible designed. DARPA has now posted on their website presentation from the Proposer’s Day. Of particular interest is a presentation from DoD spectrum managers showing how much spectrum is used by radar today."Michael Marcus, P.I." - FHH Current Issues in Telecommunications Law and Regulation

My friends at FHH CommLawBlog have written the above article in the December 2012 Current Issues in Telecommunications Law and Regulation, a newsletter based on the blog. (Apparently FHH has a law practice as a sideline to blogging. Blogging is really a lot more fun!)

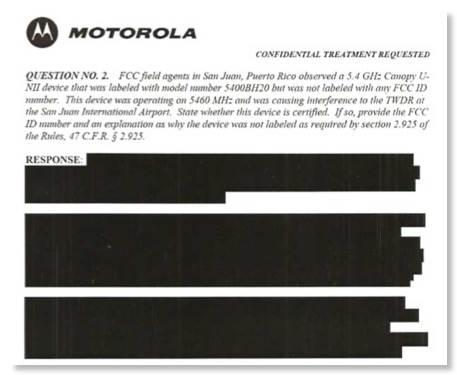

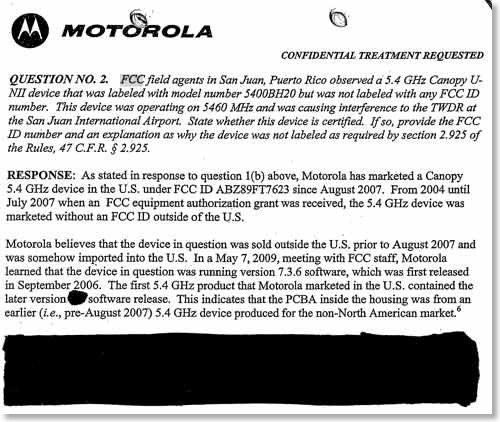

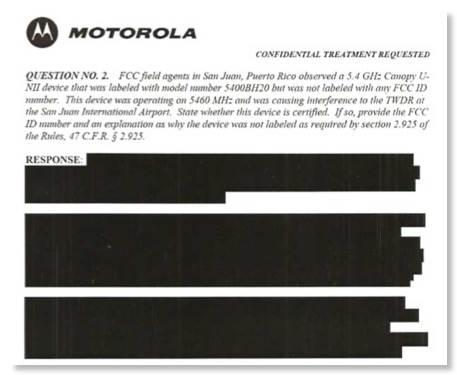

The article deals with my FOIA request at FCC to get to the bottom of the U-NII interference to safety-related NOAA TDWR weather radars near airports. This resulted in a “reverse FOIA” action by Motorola seeking to limit the release of information for what was said to be protection of proprietary information but which appeared to be based in some part on just preventing embarrassment.

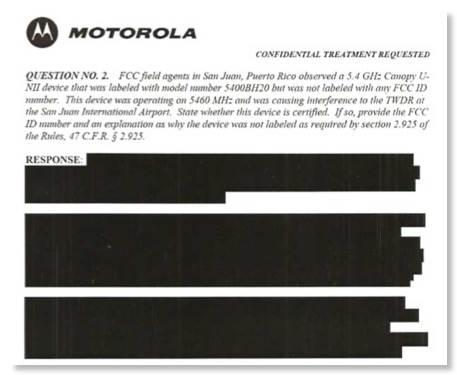

Original Motorola Redaction Initially Upheld by FCC Staff

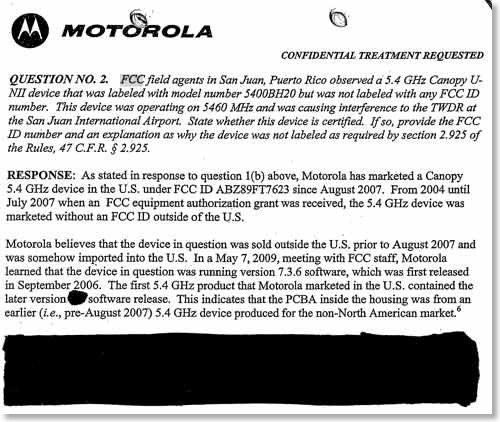

Redaction After FCC 9/12 Order

FCC ultimately upheld part of your blogger’s request giving Motorola the type of defeat that used to be very rare for them when they dominated (monopolized?) the mobile radio biz.

Here’s part of what FHH wrote:

In our recent blog post on our CommLawBlog site about an AT&T wireless Internet service causing interference to an airport weather radar in Puerto Rico, we asked whether the FCC had charged AT&T with the wrong offense. Because the transmitter operated outside its FCC- certified frequency range (among other problems), the FCC determined it did not qualify for unlicensed operation, and so fined AT&T for not having a license – even though AT&T could not have obtained a license for that service.

Our friend Michael Marcus, a spectrum-savvy engineer (and former FCC official), asked a different question: how did the transmitter get to be operating on a non-certified frequency? Where most of us would be content to mull this over in our idle hours (if it occurred to us at all), Marcus is made of different stuff. He not only took the question to the highest reaches of the FCC, but managed to get some answers.

The article goes on to say

Marcus appealed that decision to the full Commission, ask- ing for access to specific redacted information. He argued, in part, that release of the information is in the public interest because it may shed light on the root causes of interference from the Canopy transmitters into airport radars, and thus promote air safety. The FCC’s decision gave Marcus a partial victory.

Thanks to FHH for the free press.

FOIA Practice @ FCC: Is FCC Consistently Over-redacting?

Here we see that FCC initially accommodated Google’s request to redact a phrase because it was “proprietary”, but the unredacted text later released by Google when public pressure was too great shows that what was involved was not proprietary information covered by FOIA Exemption 4, rather it was just wrongdoing that was embarrassing to Google.

Recently, FCC finally issued an Order on your blogger’s appeal of Motorola’s redaction of a letter they sent FCC in response to questions about interference to safety-related weather radars that was caused by Motorola equipment. (Motorola has since sold the division involved.)

Original Motorola Redaction Initially Upheld by FCC Staff

Redaction After FCC 9/12 Order

Motorola insisted throughout this struggle that the whole response to the above Question 2 was subject to FOIA Exemption 4. As in the Google case, readers might want to contemplate if Motorola had any rational justification to say that the 2 paragraphs now (mostly) unredacted was really "trade secrets and commercial or financial information obtained from a person [that is] privileged or confidential" or was it just embarrassing?

The new FCC Order stated that two sections of the Motorola letter in question remain completely redacted. In view of the information revealed in the above lesser redaction, one wonders if those redactions are really proper. Is FCC just too ready to accept corporate request for redactions without making real public interest determinations?

Your blogger intends to appeal the 9/12 Order and would welcome any pro bono legal help in such an appeal.

FCC FOIA processing has had some criticism from the right wing recently. The Daily Caller recently had an article entitled “FCC FOIA denial rates higher than CIA for ‘records not reasonably described’” based on numbers recently revealed by Florida House Republican Mario Diaz-Balart. Raw data is available at 2011 FCC FOIA report.

reason.com alleges

“What's the quickest way to get a FOIA request returned by the FCC? Try asking it for information about a political enemy of the Obama administration.”

In less than a month Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington — a group funded in part through the philanthropy of left-wing billionaire investor George Soros — obtained 233 pages of records on Rupert Murdoch and his News Corp. media empire, from between Jan. 1, 2006 and July 15, 2011, according to documents available on CREW’s Scribd account.

It appears that FCC is more protective about Google and Motorola than Rupert Murdoch.

UPDATE

Our friends at CommLawBlog now have a post on this issue entitled “FOIA Request Turns Up Info on Non-FCC-Compliant Transmitters”. Here are some quotes:

Because the transmitter operated outside its FCC-certified frequency range (among other problems), the FCC determined it did not qualify for unlicensed operation, and so fined AT&T for not having a license – even though AT&T could not have obtained a license for that service. Our friend Michael Marcus, a spectrum-savvy engineer (and former FCC official), asked a different question: how did the transmitter get to be operating on a non-certified frequency? Where most of us would be content to mull this over in our idle hours (if it occurred to us at all), Marcus is made of different stuff. He not only took the question to the highest reaches of the FCC, but managed to get some answers….

The mystery continues, as does occasional interference to airport radars. Users of the Canopy transmitters have no easy way to check the operating frequency or the presence of DFS capability. But those within the U.S. can – and should – look for an FCC ID number on the unit. If the number is missing, the user is on notice that the device is not only unlawful, but also a potential threat to air safety. For the sake of all air travelers, please turn it off

Motorola Wages "Reverse FOIA" Fight on Explanation of Interference from Motorola Product to Safety-related Weather Radar

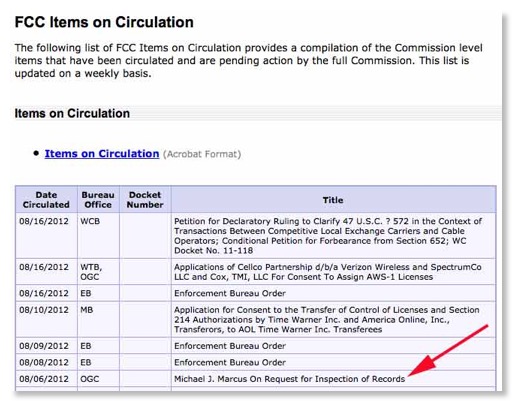

Observers of the FCC’s minutia have noticed that your blogger’s name is now on the FCC’s “Items on Circulation” list for the 2nd time. This post explains why: A FOIA request I filed on behalf of this blog and the public interest is being blocked to a considerable degree by a “reverse FOIA” campaign from Motorola dealing with a product line it sold last year.

The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit has defined a "reverse" FOIA action as one in which the "submitter of information -- usually a corporation or other business entity" that has supplied an agency with "data on its policies, operations or products -- seeks to prevent the agency that collected the information from revealing it to a third party in response to the latter's FOIA request."

So here are the basic facts:

- On August 11, 2011 I submitted a FOIA request to FCC for Motorola’s response to an Enforcement Bureau Letter of Inquiry (“LOI”) in EB-09-SE- 064, the investigation of U-NII interference to Terminal Doppler Weather Radar (TDWR) , a safety-related system to detect severe storms near airports, near the San Juan International Airport. This document was cited in an April 2010 Consent Agreement between Motorola and FCC where Motorola “agree(d) that it will make a voluntary contribution to the United States Treasury in the amount of $9,000” and make some management changes and FCC agreed to terminate the investigation.

- Rather than getting a response from FCC, I got a response from Motorola that included a severely redacted copy of their letter to FCC. (Those of us who worked at FCC know that it was traditional for FCC to give “professional courtesy” to Motorola in the past.) Much to my surprise, a September 9, 2011 letter from FCC’s Enforcement Bureau simply ratified Motorola’s redactions, part of which are shown below:

Motorola redactions of their response to FCC/EB which included a request for the FCC ID number of the unit involved and a question about whether it was properly certified. Is this really proprietary information?

- On September 23, 2011 (nearly a year ago) I filed a timely appeal of these excessive redactions under the provisions of 47 C.F.R. §0.461(i)(1). Motorola engaged Wiley Rein (“Broadcasting & Cable has recognized Wiley Rein as a ‘powerhouse law firm.’ “ ) to wage a reverse FOIA fight to protect all the original redactions.

- While it is generally felt that the FOIA legislation requires redaction of proprietary information, the Supreme Court held in Chrysler Corp. v. Brown that "Congress did not design the FOIA exemptions to be mandatory bars to disclosure" and that the agency could release information in the public interest.

A major reason for my request for this information is not voyeurism and has been discussed here previously: the software defined radio (SDR) rules adopted in Docket 00-47 were modified shortly afterwards in Docket 03-108 at the request of several manufacturers including Motorola. These changes watered down the software security provisions for SDRs. As a result of these concerns, the former 2.932(e) was replaced with the present 2.944 which does not apply to transmitters unless the “software is designed or expected to be modified by a party other than the manufacturer”. It is your blogger’s guess that the root cause of this series of interference incidents is this rule change.

While Motorola, and hopefully the company that now makes the Canopy products in question, are bound by the Consent Agreement and are unlikely to repeat the actions that resulted in this dangerous interference, other manufacturers of radios implemented with SDR technology are still only bound by the vague terms of the present §2.944 and might take similar actions to what Motorola did and is now trying to hide in this reverse FOIA action. Is it in the public interest to see what the root causes of this problem were and if necessary take steps to prevent any other firms from doing what Motorola employees did here?

Readers may recall a recent FOIA controversy at FCC involving Google. In that case Google told FCC to release only a highly redacted version of its “Spy-Fi” report which was done on 4/13/12. Under blistering criticism, Google released the report with minimal redactions - the only remaining redactions appear to be identities of people interviewed.

Google’s original redactions of “Spy-Fi” FCC report along with the unredacted text released by Google after public outcry. Large corporations, like government agencies, sometimes try to hide their misdeeds from the public by misusing information disclosure laws.

Motorola has changed a lot in the past 2 decades. The Canopy device involved in this controversy is part of a product line that was sold to Cambium Networks in September 2011, about the time this FOIA battle started. The remaining publicly owned company, Motorola Solutions, focuses on the Part 90 market with public safety being a key customer. (“Motorola Solutions serves both enterprise and government customers with core markets in public safety government agencies and commercial enterprises” ref.) Motorola Solutions has a set of publicly stated values that includes:

Motorola Solutions, is it really worth risking your reputation with your current customer base on this issue and the vagaries of the 8th Floor? I have offered repeatedly to settle this FOIA issue through discussions and recognize that the document in question has some valid trade secrets. Google made a wise decision to err on the side of disclosure, perhaps you should also. Your counsel knows how to reach me.We are accountable. We stand behind the work we do, the contributions we make and the high business standards we maintain.

Public safety users, do you really want to depend on an infrastructure provider that doesn’t meet the standard of transparency that Google set with respect to admitting practices that resulted in safety-related interference? Perhaps you should press Motorola to come clean on what really happened in San Juan?

UPDATE

FCC has now released an Order supporting some of your bloggers requests to remove redactions and upholding Motorola’s requests for redaction on other issues. However, the final redactions have not been released yet and any decision to appeal further will depend on the nature of the final redactions.

FCC's Ambivalent Views on Equipment Enforcement

Last week I gave an invited talk at the American Council of Independent Laboratories” (ACIL) 2012 Policies & Practices Conference. ACIL is the trade organization that represents private testing labs including the ones active in the FCC’s equipment authorization program, which FCC describes as

“The FCC oversees the authorization of equipment using the radio frequency spectrum. These devices may not be imported and/or marketed until they have shown compliance with the technical standards specified by the commission.”

The talk was entitled “Enforcement in the Digital Age”. Readers may recall that equipment marketing enforcement has been a recurring theme in this blog. While FCC sometimes lashes out with dramatic equipment marketing enforcement actions, in general FCC seems to turn a blind eye to such enforcement issues, relying almost exclusively on a complaint-driven process. FCC bureaucrats have learned that enforcement usually makes somebody angry, the perpetrator, who then hires a big law firm. Unless there is somebody who is pleased by the enforcement, a big complainant for example, the principle of “aggravation minimization” dictates don’t get involved.

Oddly, the major trade associations, NAB, CTIA, TIA, and CEA, seem to have little or no interest in equipment enforcement, except perhaps for the case of jammers. As a result there is essentially no independent surveillance of marketing of noncompliant equipment other than the recent (long overdue) initiative on cellular and GPS jammers. Enforcement Bureau staffers do not spot check retailers for noncompliant equipment. They don’t even go to the annual Consumer Electronics Show. There is a small amount of market surveillance by TCBs, but, as discussed in slides 16-17 this is minimal and hopelessly affected by intrinsic conflicts of interest.

The FCC Lab does not routinely call in equipment for post approval testing or ask manufacturers for copies of test data for equipment subject to Verification or Declaration of Conformity. During my tenure such events were very rare and may well continue to be very rare. Indeed, as I pointed out in my talk (slide 18 ), the labels on equipment subject to Verification or Declaration of Conformity do not necessarily contain enough information to even identify who the “responsible party” is that is supposed to have the test data. This if a suspicious unit were to be bought at a retailer - another unlikely event - it can be difficult to trace the source under present rules.

The issue of “lab queens” was discussed (Slide 15). “Lab queens” does not refer to the possible life style of FCC employees, rather it refers to test samples of equipment that are atypical of the actual production equipment. This could result from either testing many units and selecting the one with the best performance or by intentionally modifying a production, for example to decrease its power. This actually happens and so far has never resulted in a major penalty. I proposed criminalizing this behavior by requiring a sworn affidavit from a US resident stating that the unit was normal production unit taken from normal inventory. Further I proposed that FCC be authorized to request a “coupon” good for a unit of equipment at any retail dealer. This would allow FCC for the first time to get reliable samples of production equipment for sampling.

I pointed out that FCC keeps saying that it will modify its rules quickly when new types of equipment-related interference are actually encountered. This is just not credible. In the case of police radar detector interference to VSAT systems it took over 10 years for FCC to react. In the ongoing case of interference from early generation bidirectional cellular amplifiers if has taken more than 5 years and there still is no action so marginal manufacturers can still make the original designs although reputable manufacturers have eliminated the problem through design changes. I urged a regular public report on “emerging interference issues” which are not even well disseminated within FCC staff at present. (Slides 9-10)

Presently unregulated amplified

TV antenna with 55dB gain!

I ended the presentation with an open question: why do the major trade associations with an apparent interest in orderly spectrum use (CTIA, NAB, TIA, CEA) remain so silent on the issue? Is reasonable progress possible?

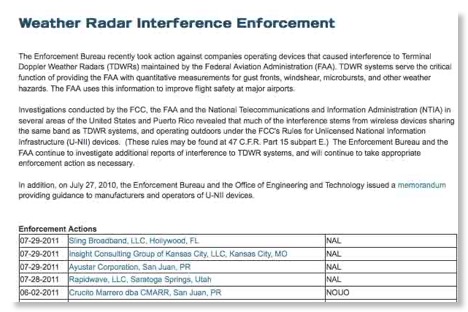

U-NII/Weather Radar Interference Update

The FCC/EB webpage linked to the picture above now lists 17 FCC enforcement actions related to U-NII interference to FAA TDWR weather radars since 2007. For those not familiar with the jargon here, a March post here reported how 5 GHz unlicensed U-NII equipment operating in the 5.47-5.725 GHz band are required to have dynamic frequency selection (DFS) as defined by 15.407(h), basically a listen-before-talk (LBT) cognitive radio system, in order to avoid interference to several types of federal government radar systems that operate in the same band. The Terminal Doppler Weather Radar, an FAA weather radar near airports, has been receiving interference in several cases despite this requirement. The big question - Why?

NTIA/ITS recently released the second of a 3 part report series that deals with the issue as shown at left. This report has the following interesting quote:

(One)U-NII device was tested against FCC DFS certification waveforms and it did not detect any. It also failed to detect any emulated TDWR waveforms. The device, however, was FCC certified, meaning it had passed these same tests when the FCC laboratory tested its DFS performance. A firmware update from the manufacturer eventually rectified this problem, illustrating how firmware upgrades can lead to DFS non-compliance.

This strongly implies that the manufacturer changed the firmware after FCC approval. While the original FCC software defined radio (SDR) rules would have made such a software change a Class 3 Permissive Change and required regulatory review, the softening of the rules in Docket 03-108 and deletion of the former 2.932(e) gave a green light to such software changes.

Two March 2010 enforcement actions seem to confirm this. These involved Airspan and Motorola. Airspan agreed in a consent decree as follows:

Remedial Measures. Airspan has developed and distributed to its United States MicroMAX customers a software upgrade for its MicroMAXdevice that prevents users from disabling the DFS radar detection mechanism and varying any other operating parameters of the device.

Thus they were selling a unit where the users could turn off the required DFS capability needed to protect safety-related FAA radars! Airspan agreed to make a $10,000 “voluntary payment” to the Treasury as part of the consent decree.

Motorola agreed to a $9,000 “voluntary payment” but their consent decree is more cryptic than the one for Airspan or a similar one for Axxcelera Broadband Wireless, Inc. that appears to be based on a hardware component issue not a software change. The Airspan consent decree has clearly stated “remedial measures” that says what they will correct, Moto gets off with a $1,000 small “voluntary payment” (trivial to what this must have cost in legal fees), a vague agreement to train their employees better:

Motorola will train and provide materials concerning Section 302(b) of the Act and Parts 2 and 15 of the Rules pertaining to U-NII devices and the requirements of the Consent Decree to those of its employees who are involved directly in the development and marketing of U-NII devices imported, marketed and sold by Motorola in the United States.

Cryptically the consent decree states

On April 20, 2009, the Bureau issued an LOI (letter of inquiry) to Motorola. The LOI directed Motorola to submit a sworn written response to a series of questions relating to the marketing and selling of U-NII devices. Motorola responded to the LOI on May 20, 2009.

The content of Moto’s response to the LOI indicating how this happened is not on the public record. This is reminiscent of the “professional courtesy” Moto used to get from FCC when it was the dominant player in the mobile radio field and contrasts with how the lesser firms, Airspan and Axxcelera, were treated - they both paid a greater “voluntary payment” and had their violation more explicitly reported. Moto’s failings are not given in the public document, only in the referenced in the publicly unavailable 5/20/09 LOI response.

The coddling and preferential treatment of Motorola was common in the past but neglects the fact that it may have contributed to Moto’s lack of competitiveness and its ultimate demise as the top mobile radio firm. In the past Moto may have stressed its regulatory prowess over its technical prowess and was not prepared for the level playing field that cellular presented with new competitors. As Trefis reported

Motorola’s market share is expected to decline from a high of 22% in 2006 to 2.8% in 2010, [3] and could continue to decline to 1.6% by the end of Trefis forecast period(2011).

UPDATE

You blogger has filed a FOIA request for the above mentioned Motorola response to the FCC letter of inquiry (LOI) and will publish here the text when received. Today, the following interim response from FCC was received:

Your Freedom of Information Act ("FOIA") request dated August 11, 2011, was assigned to the Commission's Enforcement Bureau. You seek the response to a Letter of Inquiry ("LOI") issued in the Enforcement Bureau's investigation of Motorola, Inc. ("Motorola") (EB-09-SE-064). Motorola responded to the LOI on May 20, 2009. This email is to inform you that Motorola filed a request for confidential treatment of most of its LOI response pursuant to 47 C.F.R. § 0.459 of the Commission's rules. Since the confidentiality request is pending, pursuant to Section 0.461(d)(3) of the Commission's rules, we will serve Motorola with a copy of your FOIA request and afford them 10 calendar days to respond. Motorola also is required to serve you with a copy of its response.

The criteria for withholding such information is given in 47 CFR 0.457(d) . We patiently await word from Motorola if it is willing to let the world know why its equipment violated FCC rules or whether they will fight the release of any substantive information.

Radar/Communications Spectrum Sharing: ISART 2011

On July 27-29 NTIA will host the 12th Annual International Symposium on Advanced Radio Technologies (ISART) at its Boulder, CO Institute for Telecommunications Sciences. The theme this year is “Developing Forward-Thinking Rules and Processes to Fully Exploit Spectrum Resources” with a special focus on radar bands.

For the third time since his retirement from FCC, NTIA was kind enough to invite your blogger to speak at this important meeting, but due to a conflicting family event, he is unable to attend. However, in view of the importance of this issue, he volunteered to produce a written paper on the topic to help stimulate discussion. Here is a link to that paper.

The paper starts by stating the need for new spectrum to speed economic growth which is important for both our society and for national security. Spectrum allocation should not be viewed as a zero sum game, but it is critical to develop innovative sharing techniques to get the maximum use of this limited resource. Since radar systems are a large user of spectrum and are difficult to share with using conventional approaches, this is a very timely conference.

TDWR

The main part of the paper advocates joint design of new radar systems with communications experts in order to maximize spectrum sharing and consider financial cost sharing of features that facilitate sharing subject to the radar mission needs. Just as the stealth bomber design involved a unique team of aeronautical engineers and EEs who could trade off flying issues with radar visibility issues, joint design of radar/comm systems may well result in sharing breakthroughs. While current legislation does not allow this type of cost sharing, it is not beyond the reach of new legislation that has been discussed. The paper points out that while full duplex paired spectrum with “24/7 and 1000 ms/ 1 s” time availability has been the norm for commercial systems, the decline of voice minutes and the domination of packetized traffic means that partial time availability, synched with radar rotation, could result in productive access to radar spectrum. While nonmilitary backlobe radio have not improved in 40+ years, advances in radio astronomy antennas indicate that new designs can significantly decrease backlobe levels and facilitate sharing. Such designs are expensive, but cost sharing could address that.

if you are interested, here, again, is the link.

FCC Enforcement in Action: The Mysterious AT&T San Juan Case

The issue of FCC equipment marketing enforcement has been a recurring issue here. Mitchell Lazarus, writing recently in FHH CommLawBlog pointed out the strange case of a recent Notice of Apparent Liability dealing with alleged AT&T use of 5605 MHz in San Juan PR. The NAL states

The issue of FCC equipment marketing enforcement has been a recurring issue here. Mitchell Lazarus, writing recently in FHH CommLawBlog pointed out the strange case of a recent Notice of Apparent Liability dealing with alleged AT&T use of 5605 MHz in San Juan PR. The NAL statesAs part of its ongoing coordination efforts with the Federal Aviation Administration (“FAA”), the Enforcement Bureau received a complaint that radio emissions were causing interference on or adjacent to the frequency 5610 MHz to the FAA’s Terminal Doppler Weather Radar (“TDWR”) installation serving the San Juan International Airport. ... On December 7, 2010, agents from the Enforcement Bureau’s San Juan Office (“San Juan Office”) conducted an investigation on the roof of the Miramar Plaza Condominium Building in Santurce, Puerto Rico. The agents from the San Juan Office confirmed by direction-finding techniques that radio emissions on frequency 5605 MHz were emanating from the building’s roof, the location of one of AT&T’s U-NII transmitters, a Motorola Canopy. The Canopy model is certified for use as a Part 15 intentional radiator only in the 5735.0 - 5840.0 MHz band and is not certified as a U-NII intentional radiator.

In his blog post, Mr. Lazarus comments

In cases where a transmitter fails to match its certification, as here, the FCC usually cites the manufacturer. Going after AT&T makes sense only if the FCC thinks the transmitter was compliant when shipped, and that AT&T took it out of the box, re-tuned it to an unauthorized frequency, and turned off the DFS. That would indeed be a blatant offense. But the FCC does not accuse AT&T of doing this. The farthest it goes is to say AT&T “consciously” operated at the unauthorized frequency.

The original software defined radio (SDR) rules adopted in Docket 00-47 in September 2001 had the following requirement:

2.932(e) Manufacturers must take steps to ensure that only software that has been approved with a software defined radio can be loaded into such a radio. The software must not allow the user to operate the transmitter with frequencies, output power, modulation types or other parameters outside of those that were approved. Manufacturers may use authentication codes or any other means to meet these requirements, and must describe the methods in their application for equipment authorization.

In comments filed in Docket 03-108 this rule was challenged by several parties. The R&O states:

Motorola Canopy model #5700A number of parties support a requirement for devices to comply with the rules for software defined radios if the software and operating parameters can be easily changed post- manufacture and/or that pose a high risk of causing interference to licensed services such as public safety.

Intel states that those devices that use software defined radio as a manufacturing technique and are not intended to be modified in the field should not be required to be declared as software defined radios, and that the Commission should impose requirements on only those devices where the manufacturer intends to allow modifications in the field. Vanu, Inc., a manufacturer of software defined radios, believes that mandatory certification as software defined radios may be desirable when harmful interference may result from a foreseeable modification to the device’s software by a third party. It states that the Commission could adopt security requirements that are not limited to radios that meet the definition of software defined radios. The National Public Safety Telecommunications Council and the SDR Forum believe that the Commission’s concern should not be that a radio could be reprogrammed on an individual basis because the number of radios potentially affected that way would not be significant.

So there are several possible explanations of what happened in the San Juan case:

- an unintentional manufacturing error in software or hardware left the Canopy unit capable of operating at 5605 MHz. (Use of this frequency is only permitted if the unit has dynamic frequency selection capability to avoid radar systems. This Canopy unit does not have that capability.)

- Motorola violated its equipment authorization grant and intentionally shipped a unit capable of operating on 5605 MHz

- AT&T or a contractor modified the the software in the Canopy unit to change the frequency out of the authorized band.

So while I don’t have a lot of sympathy for AT&T in this case, it would appear that either Motorola is at fault in its sale of the Canopy unit, in which case its dealers would also be culpable or this case highlights an error in the logic used by the Commission in 2005 for watering down the former 2.932(e) requirement into the present much weaker 2.944 requirement.

It is ironic that when I spoke to the SDR Forum on a panel last year (just prior to the group changing its name to Wireless Innovation Forum) someone asked the panel if the FCC SDR security rules were too weak. I think they are and are the most likely root cause of this incident, but that is what the SDR Forum and others myopically asked for in Docket 03-108 and the FCC complied, ignoring concerns stated by Cingular/Bellsouth at the time.

Let’s hope FCC gives us a full explanation of what really happened in San Juan so we can avoid similar events in this and other bands.

While we are at it, it would also be useful for FCC and NTIA to publicly state why TDWR interference is a recurring problem given that NTIA was able to dictate the terms of the U-NII rules for the shared band. I suspect that DoD dominated the IRAC discussions of the issue and FAA naively assumed that DoD would watch out for all federal radars, not just military units, so did not realize until it was too late that TDWR was different than the military units in some key aspects.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)