The 700 MHz LTE Public Safety Plan: Some Concerns

For all its flaws, the European nations now have TETRA as their public safety network core. But the previous Motorola so thoroughly orchestrated the dissing of TETRA in favor of their preferred P25 in order to maintain market hegemony , that the US ended up with neither system. (At one point Motorola - not really the same company that exists today with that name - even tried to use its ownership on a patent used in TETRA to prevent any use of TETRA in USA. The ongoing Docket 11-69 deals with the issue of any future use of this technology in the US, not just public safety.)

Two issues dealing with 700 MHz LTE for public safety don’t get much discussion, so I will review them here:

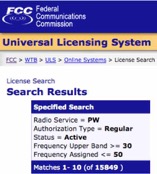

1) 700 MHz This band is comparable to one of the frequencies used for cellular telephony since the 1980s. Many of us think of cellular service as ubiquitous, but it really isn’t in terms of the land mass of the US. The map at right is the coverage area of VerizonWireless and there are certainly coverage gaps in rural areas, specially those with rugged terrain. 700 MHz has slightly better propagation than the 800 MHz cellular band, but that will not solve this problem. It is not clear if it is economically practical to cover the US with 700 MHz coverage even if the cellular industry shared infrastructure with the new public safety network. Public safety officers lives depend on ubiquitous communications. Statewide public safety agencies, as well has local and regional agencies in rugged terrain, often use the 30-50 MHz band what has much greater range than higher bands although suffers from reliability problems due to quirky propagation phenomenon and also attracts little 8th Floor interest. A ULS search reveals 15,849 current (nonfederal) public safety licenses in this long range band. (Note that Spectrum Dashboard does not cover this low policy interest band - so we can’t give you any maps.)

Now the nationwide public safety system could supplement the 700 MHz LTE systems with a more limited capability satellite (MSS) systems that provides connectivity where 700 MHz isn’t available. For example, the recently announced DeLorme inReach device uses the Iridium network and shows that limited emergency capability in isolated areas is available now at modest cost. But I have not seen any discussion about supplementing 700 MHz coverage with alternative media, such as MSS, for public safety agencies that will never have ubiquitous 700 MHz coverage in their territory. So how will the 15,849 present 30-50 MHz public safety licensees transition to the new 700 MHz system?

2) Voice over LTE Voice is an integral part of public safety communications now and in the foreseeable future. While using voice on an LTE system appears technical possible, it is not an operational reality. Last month, NetworkWorld quoted Verizon Vice President of Network Hans Leutenegger as saying that VZW “won't be deploying any voice over LTE (VoLTE) services on its network until late next year at the very earliest.” Public safety networks need not only voice, but voice with special features such as priorities, preemption, and network control by the commanders of first responders. These features are not operational as yet and it is not clear if the resources programmed for their development and testing are really adequate for the task - given the high reliability we owe our public safety officers.

More than a decade ago, the public safety community was greatly indebted to the old Motorola who invented this technology and shepherded it introduction into the public safety. Groups like APCO in the past showed their appreciation by allowing Motorola to manipulate their spectrum policy positions before FCC and they consistently opposed technical evolutions much more modest than which is involved here. Indeed, the fact that we are only now finishing the 20 year narrowband transition shows the effectiveness of this Motorola “partnership” with public safety that slowed technical progress while maintaining Motorola’s market share. The present Motorola Solutions no longer has the control of the old Motorola and others entities are trying to manipulate the public safety community for their own gains.

The fact that the public safety community generally seems happy with the present plan may indicate that the new manipulators have successfully filled the power vacuum left when Motorola was restructured. Hopefully the public safety community will become more cynical about being manipulated in the corporate interests of others and they will aggressively make sure their own interests are pursued in the development of the national wide interoperable system that is so critically needed.

Ten Years After 9-11, Still No Public Safety Network -- Wireless Week

This blog has reported repeatedly on the issue and made suggestions. So you don’t have to hear my viewpoint this time, I strongly recommend a Wireless Week interview with Gregg Riddle, who advocates for public safety workers from his post as president of APCO International, the major trade association in the public safety area. I do not always agree with APCO, but what he says in this interview makes a lot of sense.

Here is a brief excerpt:

WW: How robust are the nation's public safety networks right now? If we had another terrorist attack, would we see the same breakdown in communications we did 10 years ago?

Riddle: It's very possible because we have not addressed the interoperability concern. Public safety operations today are spread out over multiple portions of the spectrum - VHF, UHF, 700 MHz, 800 MHz and low band. They all have their own interoperability capabilities, but when you have public safety utilizing multiple portions of the spectrum, they're not easily interoperable, which was demonstrated on Sept.11, 2001.

Interoperability is critical. It was one of the Sept. 11 Commission's report items that's not been met after 10 years – interoperability for public safety. We're still struggling to meet the goal as described in the report.

There is more than enough blame to go around here both in government entities who played political games and turf battles and corporate interests who wanted to use this situation for market hegemony and their financial benefit. But this is not the time for a postmortem on who has responsibility for this mess. Rather it is the time to remember the spirit of national unity that existed 10 years ago and use it to come up with a consensus solution and adopt it.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)