FCC Official Acknowledges Pending 95+ GHz NPRM

.@FCC’s Julie Knapp: #FCC year ahead includes working on NPRM above 95 GHz

— CTIA (@CTIA) September 13, 2017

#MWCA17 https://t.co/MvwSJE6GOx

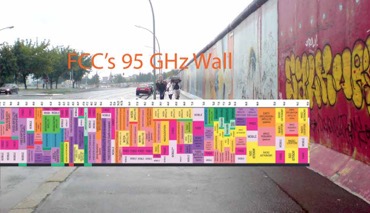

Maybe FCC's 95 GHz Wall will finally fall?

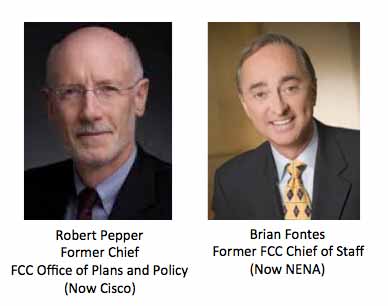

2 Unsung FCC Pioneers in Early 5G #HighBandSpectrum Policy

(UPDATE: Robert Pepper is now with Facebook)

There is an implicit viewpoint at FCC that telecom technology is like a "conveyor belt sushi"/kaitensushi /回転寿司 restaurant in Japan: you sit at the counter and various types of sushi come on a conveyor belt in front of you unordered and you just wait until you see one you like and then take it off for eating. So at FCC you just wait for telecom technology to magically come from a conveyor belt and you pick winners and ignore the losers.

Video on "conveyor belt sushi"/kaitensushi /回転寿司 in Japan from NHK

Well, telecom technology does not come by magic! It requires bright people with good ideas and then investment in R&D to work on such ideas. In radio technology, the risk of that investment and thus its commercial likelihood depends on regulatory risk of FCC approving the commercial use and hence profitability of the technology.

"it took about ten years for low-cost commercial products to evolve from 1998 (sic) when USA became the first country in the world to authorize low-power 60 GHz operation…(S)hort range wireless networks provided the relevant applications to take advantage of unlicensed 60 GHz spectrum, as well as other frequencies in the mmWave band…Due to the inherent nature of mmWave frequencies … many emerging or future mmWave wireless products and standards (such as 5G mmWave cellular, inter vehicular communications, and backhaul/fronthaul communications standards) are likely to share characteristics with the 60 GHz WPAN/WLAN standards.

Thus #HighBandSpectrum 5G did not come unsummoned from a sushi conveyor belt, but derived from earlier visionary FCC action in Docket 94-124 in the Hundt Chairmanship. In my main website I have given more background of how this came about, here let me emphasize the role of the 2 individuals shown above.

When I proposed the concept of a 60 GHz unlicensed band in late1992 to the leadership of FCC's Office of Engineering and Technology, it was immediately rejected. This was probably because of the FCC culture related to "Nobody every got fired for buying IBM", i.e. if you only do things major regulatees propose you can never be criticized. (At the time I was working in EB's predecessor FOB as part of an "internal exile" resulting from the Docket 81-413 proceeding that is now known as the basis of Wi-Fi and Bluetooth but which at the time was very controversial.)

After the OET rejection, I sought guidance from Dr. Robert Pepper - legendary Chief of the FCC's Office of Plans and Policy (now OSP) from 1989 to 2005 - an amazing tenure in a very partisan agency. Bob was interested in the idea when I presented it to him, he asked me many questions and then proposed a meeting with the Chairman's Office to discuss the issue. This was during the Quello Chairmanship and Dr. Brian Fontes, his long term staffer was his Chief of Staff. Bob came with me to the meeting with Brian and the then Chief of OET. We both gave our viewpoints and Brian agreed with me that we should start drafting an NPRM for unlicensed use of 60 GHz - far above the then upper limit of FCC radio service rules at 40 GHz. The NPRM was drafted and approved on 10/20/95 under Chmn. Hundt who succeeded Quello. The R&O was adopted on 12/15/95 and by that time both Dr. Pepper and Dr. Fontes had left FCC after many years of loyal service.

Bob is now Vice President, Global Technology Policy at Cisco. Brian is now Chief Executive Officer of the National Emergency Number Association.

I hope that the 5G community can now remember that these two gentlemen played a key role in the early development of 5G #HighBandSpectrum policy in starting the "conveyor belt" moving at a time when the cellular mainstream had little or no interest in upper spectrum bands and thus giving us the wonderful technology that was approved yesterday!

Are 5G Spectrum Deliberations at the Expense of All Other New Technology?

We will be repeating the proven formula that made the United States the world leader in 4G: one, make spectrum available quickly and in sufficient amounts; two, give great flexibility to companies that can use the spectrum in expansive ways; and three, stay out of the way of technological development. We will also balance the needs of various different types of uses in these bands through effective sharing mechanisms; take steps to promote competitive access to this spectrum; and encourage the development of secure networks and technologies from the beginning.

These statements are very admirable. But do they mean that 5G is not only FCC's highest goal but its only new technology goal at present — perhaps other than NAB's pet project of ATSC 3.0?

Is FCC interested in making new spectrum available "quickly and in sufficient amounts" for any other types of spectrum licensees - licensed or unlicensed? If 5G gets absolute priority at FCC on spectrum access, what about others needing spectrum that is not even in conflict with 5G spectrum? Are they entitled to consideration of "spectrum quickly and in sufficient amounts" if the request is noncontroversial? Is FCC spectrum policy productivity so low that only one new technology issue can be discussed at a time?

People may forget that the unlicensed ISM bands made available in Docket 81-413 were widely opposed by incumbents, even the predecessor of CEA now CTA, and had almost no corporate support in the rulemaking is now the basis of BOTH Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. There was some participation of predecessors of today's cellular carriers in Docket 94-124 that created the 60 GHz band that in turn stimulated much of the R&D responsible for #HighBandSpectrum 5G and which is about to be expanded in Docket 14-177. But they were focusing on obscure details and seemed mainly interested in computer-to-computer communications, not anything even vaguely resembling 5G. Reagan had a point when he warned against governments "picking winners and losers": Enabling 5G in a timely way should not be at the expense of slowing down all other new radio technologies not in conflict due to bottlenecks in FCC deliberative processes.

We frankly don't know what the "killer apps" technologies will be 10-20 years from now. In my most megalomaniacal phantasies in the early 1980s when I was working on Docket 81-413 I count not imagine how ubiquitous ISM band uses such as Wi-Fi and Bluetooth might become. Even the pioneers of 802.11, led by NCR which has never sold consumer electronics, thought they were developing a wireless LAN for wireless PC-based cash registers for department stores. Had they approached FCC with such a request in the absence of the Docket 81-413-developed rules I am sure they would have been politely told to go away. (Indeed, in the 1990s, before the commercial availability of Wi-Fi, Kodak approached FCC several times for a special band for downloading pictures from digital cameras to photo printing machines in camera shops and was told to go away. Ultimately Wi-Fi was capable of this functionality.)

This week UK's Ofcom released a bold NOI-like document on fixed service bands. It included the following text:

By contrast the FCC 5G proceeding has mentioned twice the possibility of other uses of #HighBandSpectrum:

There has been no further action on any uses of spectrum above 95 GHz, let alone above 75 GHz! While Ofcom acknowledges the existence of WRC-19 Agenda Item 1.15 on new allocations in 275-450 GHz, can you find any mention of this on the FCC's voluminous website?

So let's cheer the adoption of the 5G rules this week, but let's also ask whether FCC can now deal with other innovative technologies. Perhaps FCC can even explain how it will implement the provisions of § 7 of the Communications Act? Under the Chevron Doctrine FCC can do that and the courts must give deference, but FCC has given no public guidance on how it deals with new technology in the 30+ years since § 7 was enacted.

All new technologies matter and are entitled to timely consideration.

Foreign Research on Spectrum Frontiers That FCC and NTIA Block Access To

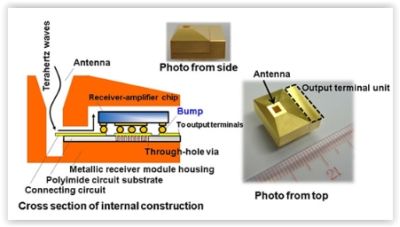

This week Wireless & RF magazine published the above article on terahertz (THz) technology R&D in Japan. While we do not necessarily believe it is now time to sell your Corning stock because fiber optic telecom is doomed, this clearly demonstrates continuing foreign interest in technology that FCC is at best apathetic about and which NTIA has allowed certain IRAC members to discourage.

While the major regulatees who routinely show up on the FCC's 8th Floor have little interest in these frequencies, these same corporations and trade association also showed little interest in Docket 81-413 that ultimately spawned Wi-Fi and Bluetooth and Docket 94-124 that stimulated the R&D that showed the surprising result that mmWave/"spectrum frontier" mobile systems were practical. Thus FCC's mainstream spectrum regulatees can sometimes be myopic and sometimes have "crystal ball" problems.

Lest you think that this article about 275+ GHz technology in Japan is isolated, here is a quote from an ETSI report last year:

“With respect to the aforementioned, the mission of ETSI ISG mWT is to promote the use of millimetre wave spectrum from 50 GHz up to 300 GHz for present and future critical transmission applications and use cases. Moreover, ETSI ISG mWT will focus on enhancing the confidence of all stakeholders and the general public in the use of millimetre wave technologies.”

Here are several other article on foreign R&D above FCC present 95 GHz service rule limit and 275 GHz allocation limit:

- Japanese 120 GHz system used at Beijing Olympics

- Japanese 72-100 GHz components

- Japanese 300 GHz receiver — Note that this article indicates that "A portion of these research results were obtained through 'R&D Program on Multi-tens Gigabit Wireless Communication Technology at Subterahertz Frequencies,' a research program commissioned by Japan's Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications as part of its 'Research and Development Project for Expansion of Radio Spectrum Resources.' " This confirms direct involvement of the Japanese regulator as part of its "industrial policy" program.

- German 237 GHz outdoor experiment - Note that the authors of this experiment have never revealed the exact upper and lower frequency limits of their transmissions and it is likely that it intruded into a passive allocation. Certain IRAC members routinely try to block such experiments regardless of whether they actually impact passive spectrum use and NTIA has not been assertive in overview of such actions.

FCC is moving ahead on Docket 14-177 on "spectrum frontier" mobile use in 28-71 GHz and that is not an issue here. The problem is that FCC has turned its "blind eye" to all other "spectrum frontier" issues while our foreign competitors are marching full speed ahead.

It gets worse! Google "terahertz spectroscopy" and you will see that there are US made products now being sold above 95 GHz for noncommunications use. A careful parsing of §302a and §2.803 of the FCC Rules reveals that the sale of such equipment is presently legal, however the use of such equipment appears to be a violation of §301 since there are no licensed or unlicensed service rules at these frequencies. The manufacturers of such equipment presently have little concern since EB is easily distracted by other mood swings and is laying off much of its field staff. But sooner or later that will need capital access and will discover what "due diligence" means! Denying such firms capital access will not help US competitiveness. FCC outreach to them will! Do you have to presently be a multibillion dollar industry to get FCC attention? We certainly can recall when Wi-Fi was a tiny industry.

Isn't it time for FCC to pay some attention to upper spectrum especially since 275+GHz allocations are on the WRC-19 agenda?

Spectrum Frontiers Workshop:

Topics Covered and Avoided

Advanced wireless connectivity in highest spectrum bands on display at FCC Spectrum Frontiers workshop tomorrow https://t.co/idaohfNa68

— The FCC (@FCC) March 9, 2016

On March 10, 2016 FCC held a workshop entitled "Workshop and Tech Demonstration on Spectrum Frontiers and Technological Developments in the Millimeter Wave Bands". The original announcement clarified this a little by saying "exploring the concepts raised in the Commission’s Spectrum Frontiers NPRM and the state of technological developments in the millimeter wave (mmW) bands". The video of the workshop is now available on the FCC's website.

But while the "state of technological developments in the millimeter wave (mmW) bands" was promised, it reality only mobile 5G mmW technology was discussed along with some other 5G issues. Numerous times numerous speakers mentioned "500 MHz" - the goal for reallocation of spectrum to cellular at lower bands. There was't even any discussion of mmW-based backhaul for cellular with the implicit assumption that fiber would miraculously be available for high capacity mmW base stations. (While fiber is the cheapest medium for high bandwidth communications based on equipment costs and while FCC is pushing "dig once" policies, the reality is that fiber is not always everywhere. New fiber installation can be extremely expensive if the costs are not shared with other users or if needed quickly for base station installation. Indeed the term "self-backhaul" is used in Europe for the potential of doing some backhaul in the same band as mobile links was never even mentioned! (Self-backhaul would not be feasible in lower bands but is plausible due to the small wavelengths and high directionality of small antennas at mmW.)

But while "500 MHz" was an allowed diversion of the discussion, any use of spectrum above 71 GHz was not. Contact with several speakers revealed that they were urged to stick to the 5G agenda and not even mention any other topics. So while the mention of "500 MHz" and lower 5G bands was acceptable and the presence of Starry, Inc and FirstNet with totally unrelated topics was acceptable, any mention of fixed use - even for cellular backhaul and any mention of the FCC 95 GHz wall appears to have been verboten! Indeed, nothing was even mentioned above the 71 GHz limit in the Docket 14-177 NPRM. The last panel of federal speakers seemed to focus on either general issues or issues that related mainly to cellular spectrum under 6 GHz.

Present FCC rules have no provisions for licensed or unlicensed above 95 GHz and petitions for such move at a glacial pace while other countries subsidize such R&D

But as we have mentioned previously FCC's barrier to innovation at 95 GHz is quite real. The FCC's inaction on Battelle's RM-11713 102-109.5 GHz petition as well as the IEEE-USA request for a declaratory ruling (Docket 13-259) above on whether technology above 95 GHz is "new technology". (Not to mention the 2.5 years it took for FCC to untangle its apparently unintended wording in the revised Part 5 rules that forbid all experiments in passive bands (which are numerous in the mmW region) regardless of whether the nature of the experiment posed an actual interference threat to passive users.)

While we do not begrudge CTIA members access to mobile spectrum up to 71 GHz or even higher, does CTIA and its wishes like Donald Trump "suck all the oxygen out of the room"? We acknowledge that FCC has a spectrum policy productivity problem, but if that is the issue shouldn't FCC also acknowledge it and show what impact it is having on US competitiveness?

The basic reason why 5G mmW technology is even here now is that FCC took visionary action in 1995 in Docket 94-124 creating the first 60 GHz unlicensed band in the world and in 2003 in Docket 02-148 establishing the world's first 70/80/90 GHz bands just as it took action in 1985 creating the unlicensed ISM bands that are now home to Wi-Fi, Bluetooth and myriad other systems that have changed our world. When FCC took these three decisions they were not in response to major trade association like CTIA, indeed, some trade associations, including CEA/CTA's predecessor, actually opposed the 1985 decision.

It was because FCC stayed true to its original §303(g) mandate and had the confidence to prepare for the future — not spend all of its resources reacting to requests for instant gratification from powerful groups.

Status of IEEE-USA Petition at FCC

Comm. O'Reilly's Post on "Defending Capitalism in Communications"

American capitalism, and its role in the communications industry,[1] should be embraced, celebrated, and exported throughout the world. Instead, it is under continuous assault domestically by self-defined progressives and ultra-liberals, who have found sport in using misguided rhetoric and false pretenses to denigrate one of the core tenets of American society. They demonize company executives, decry profits and income, promote class warfare and push policy positions favoring government-provided services over private sector solutions. Beyond being disingenuous and inflammatory, these views completely ignore the extraordinary benefits that the American capitalistic system brings to communications services.

Without proper checks and reassertion of our commitment to free enterprise, the latest anti-capitalism talk risks seeping into Commission proceedings and underlying activities. In fact, signs of it can be seen in multiple Commission proceedings, from municipal broadband advocacy to the harmful net neutrality overreach. The following briefly explores just some of the benefits of capitalism.

There are then 5 sections:

1. Connects Willing Buyer and Seller in Marketplace

2. Minimizes Need for Government Interference

3. Protects Consumers Efficiently and Sufficiently

4. Facilitates Profits and Economic Growth

5. Fosters Entrepreneurialism

Your blogger has posted this comment to Comm. O'Reilly's posting

You did not explicitly mention the issue of technical innovation and FCC, but I think this is consistent with your general view. Despite decades of FCC deregulation enabling "permissionless Innovation" there are technical areas where FCC has not been able to develop such a framework. Some technical innovations still require "Mother, may I .." requests to FCC.

Thus the iPhone was introduced with only fast routine FCC approvals but the issue of ANY use radio technology above 95 GHz is the exact opposite requiring non routine approvals with no particular time schedule. While many criticize FDA New Drug Approval procedures, FCC's procedures for new technology requiring unusual approvals is worse in many ways. At least FDA has nominal schedules for NDAs and tells applicants what is needed in their requests

FCC has had before it a petition for a declaratory ruling from IEEE-USA on the issue of whether technology above 95 GHz should be presumed to be "new technology" in the context of Section 7 of the Communications Act. (Note that since 2003 FCC's radio service rules have ended at 2003 GHz and therefore new rules are needed for any type of licensed or unlicensed transmitter above that frequency.) This petition was filed in July 2013 and in January 2016 it was revealed that 2.5 years after filing it is circulating on the 8th Floor. TRDaily reports that the draft says that Section 7 requests should always be handled on a "case by case" basis. Oddly in the 30+ years since Section 7 was signed into law by President Reagan FCC has not found one "new technology"!

A basic precept of capitalism is that innovators should be able to get new products and services to market in a timely way and let the marketplace decide on their merits. Many people agree that this should be tempered somewhat for products and services that may cause harms. But the endless delays that FCC imposes on new technologies not in areas subject to "permissions innovation" are generally independent of harms to others.

FCC has pledged to deal with corporate mergers on a timely schedule with online status tracking. As far as I am aware there is no statutory mandate for this timely consideration but FCC has chosen to do it as a matter of good public policy. However, Section 7 does give a clear legislative mandate that "It shall be the policy of the United States to encourage the provision of new technologies and services to the public. Any person or party (other than the Commission) who opposes a new technology or service proposed to be permitted under this chapter shall have the burden to demonstrate that such proposal is inconsistent with the public interest." Further Section 7(b) requires " The Commission shall determine whether any new technology or service proposed in a petition or application is in the public interest within one year after such petition or application is filed." This is not a perfectly drafted piece of legislation, but are all other parts of the Communications Act that much clearer?

For 30+ years under leadership of BOTH parties FCC has been trying to dodge these mandates. FCC has never asked Congress to modify or clarify or even remove them.

Is this timeliness needed? Look at the examples given by Mitchell Lazarus, a prominent communications law practitioner specializing in innovative radio technology, in his comments in Docket 09-157 of noncontroversial radio innovations that were delayed for years.

Look at the Petition for Rulemaking filed by Battelle Memorial Institute more than 2 years ago for use of a 105 GHz point-to-point system in a band beyond the FCC's 95 GHz limit but consistent with all US spectrum allocations. While this has been mentioned in both the NOI and NPRM in Docket 14-177 there has been NO action on either implementing the proposal or rejecting it. Meanwhile our foreign competitors are targeting spectrum above 95 GHz for commercial use with industrial R&D support and with proposals adopted at WRC-15 (without US participation) to create new ITU spectrum allocations in 275-450 GHz at WRC-19.

Thus the concepts of capitalism require that new products and services must get a timely market test unless there is a real reason to stop them. While many such products and services are now subject to "permissionless innovation" at FCC, many are not. FCC should implement procedures to deal with them in a timely way or be prepared to give technical leadership to our foreign competitors.

WRC-19 to Address Allocations Up to 450 GHz

In October we published a post here entitled

This dealt with proposals from European and Asian ITU members to put on the WRC-19 agenda new allocations up to 450 GHz and 1000 GHz, respectively. As far as we can tell the US WRC-15 was totally blindsided by this issue and had no position on it going into this year's conference. We believe that this is partly due to a fundamental flaw in US WRC preparation at both FCC and DOS that is nominally transparent but in actuality is stacked in favor of deep pocket major entities with little or no outreach to other US interests.

The main US deep pocket entities are focused, like most of US industry, on near term gains. They are not apposed to moving the upper limits of spectrum allocations above the present 275 GHz and probably do not even oppose new FCC service rules above 95 GHz, but don't want it to detract from their near term gratification at lower frequencies. Thus given limited resources at FCC and DOS such long term issues get little or no attention.

So as a public service we are linking here to the agenda item for WRC-19 that deals with new allocations in the 275-450 GHz range in the hope that it stimulates interest when WRC-19 preparation begins.

Europe and Asia Propose Extending ITU Radio Regulations to 1000 GHz at WRC-19

US Silent

FCC stalled at 95 GHz

Our friends at the UK's PolicyTracker, a spectrum-focused newsletter with world wide coverage, have given us kind permission to reprint the article below by Toby Youell that first appeared on their website on October 2.

Radio Regulations may be extended up to 1000 GHz at WRC-19

Two proposals for new agenda items at WRC-19 could lead to the Radio Regulations extending the upper limit for transmissions from 275 GHz to as much as 1000 GHz.

These frequencies are currently only governed by a footnote (5.565) that allows for the protection of receive-only applications such as the radio astronomy, Earth exploration satellite and space research services.

But according to a new proposal from the Asia Pacific Telecommunity, the ITU-R should “study potential candidate frequency bands for use of the land mobile and fixed services” between 275 GHz and 1000 GHz. Similarly, Europe's common proposal for agenda items at WRC-19 invites the ITU-R to “identify candidate frequency bands for use by systems in the land mobile and fixed services” in bands up to 450 GHz.

Gerlof Osinga, vice chairman of the European (CEPT) conference preparatory group, told a recent ITU inter-regional workshop on WRC-15 preparation that the 450 GHz limit was intended to limit the amount of work that would need to be done in the next study cycle.

According to both draft resolutions, using frequencies higher than 275 GHz may become viable as technology develops. Ultra-high-speed data communication systems demonstrated by some research and development organisations can already transmit at a speed of 100 Gbps above 275 GHz, CEPT says. IEEE task group 802.15.3d is developing standards for wireless personal area networks (WPANs) at these frequencies. One use case could be wireless links in data centres.

Initial studies of technical and operational characteristics of services operating in the 275–1000 GHz range have been undertaken by ITU-R Working Party 1A, while ITU-R Study Group 3 has studied the propagation characteristics of these bands. But according to documents submitted for WRC-15, sharing and compatibility between passive services and potential active applications in the bands has not yet been studied at ITU level.•

In view of the pending "Spectrum Frontiers" NPRM at FCC, why can't FCC think beyond the present 95 GHz upper limits of FCC radio service rules - a limit that was reached in 2003.

Discussions with FCC/IB staff have confirmed there is nothing comparable to this in US proposals. Does this indicate a structural flaw in US WRC preparation process? We think so as this is not the first time that US WRC proposals have focused in cliques well represented in WRC preparation and ignored other public interest issues. More later.

UPDATE

The CEPT and APT proposals for new spectrum beyond the present 275 GHz ITU limits can be downloaded here.

Chairman Wheeler, tear down that wall!

What will it take for FCC to break the 95 GHz ceiling in the "Spectrum Frontier" NPRM?

On October 16, 2003 in the Report and Order of Docket 02-146, FCC raised the upper limit of its radio service rules to 95 GHz. They have remained there ever since. The table below from the FCC Allocation Table, §2.106, shows the spectrum allocations and service rules from 86 to 105 GHz. Note the orange circle we have added to emphasize the lack of rules above 95. (Actually there are two small and narrow exceptions: amateur radio use and ISM use.)

Chairman Wheeler last week announced "rebranding" the Docket 14-177 NOI in a "Spectrum Frontiers" NPRM that will be considered at the 10/22 Commission meeting. He stated:

This NPRM proposes a framework for flexible spectrum use rules for bands above 24 GHz, including for mobile broadband use. Promoting flexible, dynamic spectrum use has been the bedrock that has helped the United States become a world leader in wireless.

We are leveraging regulatory advances and propose to use market-based mechanisms that will allow licensees to provide any service – fixed, mobile, private, commercial, and satellite – depending on the band, and allow unlicensed uses to continue to expand. We are proposing to create a space that leverages the properties of this high band spectrum to simultaneously meet the needs of different users.

We hear from usually reliable sources that the NPRM will follow the NPRM and ignore the comments in keeping the bands considered under 95 GHz. In an August statement Chmn. Wheeler wrote

Our sources report nothing has changed. Furthermore despite the phrase "for a wide variety of users" the NPRM is expected to focus on the needs of CTIA members. We do not think it is inappropriate to provide new spectrum for such carriers, even though many are frankly ambivalent. (VZW did not even bother to file reply comments.) But what about other possible users?The spectrum bands proposed by the United States to be studied for consideration at WRC-19 include 27.5-29.5 GHz, 37-40.5 GHz, 47.2-50.2 GHz, 50.4-52.6 GHz, and 59.3-71 GHz. We will consider these bands, or a subset of the bands, in further detail in an upcoming NPRM, with the goal of maximum use of higher-frequency bands in the United States by a wide variety of providers.

What about broadband fixed links between locations where fiber installation is very expensive? (The fiber and electronics for fiber optic systems are inexpensive leading to a low cost/bit/mile if you exclude installation cost. But in urban environments installation costs can be huge for new fiber.) Millimeterwave fixed systems can serve such applications with a higher hardware cost, but lower total cost than fiber optics. Yet they face the same 95 GHz barrier!

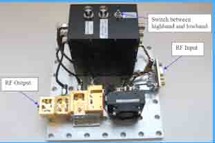

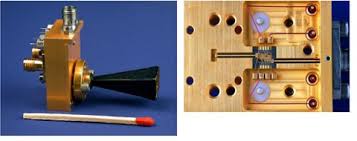

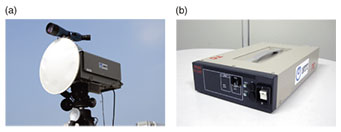

Why not also remove regulatory uncertainty from the manufacturers who are providing gray market equipment for non communications uses such as Terahertz spectroscopy? For example at left is a 575-560 GHz source sold by a US firm for THz spectroscopy and at the right is a Japanese system for use at 60 - 4000 GHz. These exist in a Title III "Never Never Land" with respect to their legality. Clearly they are not a target of the rapidly shrinking spectrum enforcement operation at FCC, but any investor doing due diligence would be thoroughly puzzled about the regulatory status of such technology. Such uncertainty is a disincentive to private capital formation which may explain why the more elegant device above comes from a Japanese firm.

In recent months ETSI, a nominal "standards organization" that includes most European counterparts of FCC, released the above report which is basically a master plan for millimeter wave development by Europe, Inc. while FCC stalls at 95 GHz. The applications considered in the ETSI report include both those of cellular carriers and other applications. They do not have tunnel vision focused solely on the needs of CTIA's European counterparts and spectrum below 71 GHz. (Does the Commission remember that in 1985 all the key industry players all opposed the Docket 81-413 rulemaking that is now the basis of both Wi-Fi and Bluetooth?)

Indeed, if FCC is at a loss what to do, maybe it should just propose endorsing the ETSI report? This would significantly reduce regulatory risk for US entrepreneurs!

Both the FCC's Asian and European counterparts, APT and CEPT, are proposing for WRC-15 new agenda items for WRC-19 that would go far beyond FCC's present technological meekness. APT proposes to "study potential candidate frequency bands for use of the land mobile and fixed services” between 275 GHz and 1000 GHz while CEPT proposes to “identify candidate frequency bands for use by systems in the land mobile and fixed services” in bands up to 450 GHz. FCC just can think beyond 95 GHz! Why?

Europe and Japan March Ahead in Millimeterwaves with their State Capitalism Spectrum Model While FCC Hesitates

We have previously written about the FCC's "War on Millimeterwaves" - the inaction on moving the upper end of spectrum regulation above 95 GHz where it has been since 2003. Why invest in such new technology when you have no idea when FCC will allow market access? There are lots of other new technologies out there, some FCC regulated and others with different types of regulation, where either no government approvals are needed for new technology or where the needed approvals are both timely and transparent. Unless you are a masochist, why limit yourself to FCC-regulated technology and certainly why invest in a technology where there is "no light at the end of the tunnel". FCC's "blind eye" to the statutory requirements of Section 7 of the Communications Act to act in a timely way on "new technology" isn't helping either.

So let's look at what our national economic competitors are doing. The new report shown at the top of this page is from ETSI, the European Telecommunications Standards Institute. While this might sound like ANSI, its US counterpart, ETSI is really very different in that Europe's telecom regulators are key members and CEPT, the organization of Europe's "FCC's" had a key role in starting it. Also note that in Europe national and EU regulations often permit the use of equipment meeting ETSI standards, e.g. GSM and DECT, and forbid alternative technologies such as those developed and sold in the US.

In this document Europe Inc is making a roadmap for millimeter wave technology and it is clear that the same Europe Inc. is subsidizing the R&D of this technology. Here is part of the discussion of what this technology can be used for:

A variety of wireline as well as wireless technologies are available to build transmission infrastructures and usually a mixed environment of physical media is adopted. While optical fibre is perceived as the physical medium with the top performance, there are techno-economic factors that make installation or even extension of optical fibre network not always the most appropriate solution. Hence, wireless technologies represent today a significant or even a dominant percentage of various operators' transmission networks to serve efficiently the increasing upward trend for providing data-hungry applications.

While microwave solutions at traditional bands are more or less employed by all kinds of service providers (mobile, fixed), it becomes clear that moving to millimetre wave frequency bands, where underutilized massive bandwidth is available, will assist to deliver transmission services of equal to optical fibre performance avoiding the constraints that the latter might impose at particular scenarios. In this sense, millimetre wave frequency bands can be used in an immense number of current and future high-speed wireless transmission applications.

While FCC Docket 14-177 deals with mobile applications above 24 GHz, the NOI seems to go out of its way to deal only with mobile uplinks and downlinks issues, even though now mobile systems will need lots of infrastructure and backbone, much of which is a target for mmWaves. In any case, while UK's Ofcom has been much faster than FCC on its counterpart of 14-177, the FCC next action is still a few months away.

This week we have news from Japan on Fujitsu's development of a new 300 GHz receiver, shown below:

Note this section from the linked Fujitsu news release:

A portion of these research results were obtained through "R&D Program on Multi-tens Gigabit Wireless Communication Technology at Subterahertz Frequencies," a research program commissioned by Japan's Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications as part of its "Research and Development Project for Expansion of Radio Spectrum Resources."

Yes, Japan, Inc. is partially funding this R&D through the very same agency that is FCC's Japanese counterpart! Now do you think Fujitsu is losing sleep about regulatory delay when it is ready to market this technology?

Such state capitalism is not the US system and should not be the US system. But in highly regulated areas like spectrum how can US entities compete against Europe, Inc. or Japan, Inc.? The answer is increasing transparency of spectra policy as well as its timeliness.

Why is Qualcomm a US company? Qualcomm was incorporates in July 1985 a few months after the May 1985 Docket 81-413 decision that permitted general use of sported spectrum in 3 unlicensed bands. According to cofounder Viterbi this stimulated the capital formation needed to get things rolling and within 2 years Qualcomm got FCC approval for its CDMA cellular technology - unbelievably controversial at the time.

At the end of the Declaration of Independence are the words "we mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes, and our sacred Honor.” Qualcomm founders Viterbi and Jacobs may not have pledged their "lives" to get the company founded, but they certainly pledged their "fortunes" and "sacred honor" as 2 major leaders of communications theory and technology at the time. But they were able to get timely and transparent treatment from FCC at that time and a major company now results that contributes to US leadership in telecom technology.

Let's face up to the reality of state capitalism in our economic competitors and see what can be done to "level the playing field". I think speed and transparency for new technology would be a good step. Who knows, maybe even FCC compliance with Section 7 of the Communications Act after these many years might be nice step?

FCC Approves MSS Part 5 Reconsideration Request

On July 8 FCC released an MO&O&FNPRM in Docket 10-236, formally captioned “Promoting Expanded Opportunities for Radio Experimentation and Market Trials under Part 5 of the Commission's Rules and Streamlining Other Related Rules”. This decision deals with 3 reconsideration requests, one of which was filed by your blogger. They relate to the January 31, 2013 FCC decision to revise the experimental licensing rules. In that decision the new rules forbid for the first time all experimental licenses in bands with only passive allocations. While this language had been in the NPRM’s draft rules, it was never mentioned in either the discussion sections of the NPRM or the R&O and quite probably was a drafting error.

We got involved in this issue after signing a new client in May 2013 who was having problems getting experimental licenses for millimeterwave technology experiments. In researching the issue, we noticed that the new rules were about to go into effect that would have made the task nearly impossible due to a new prohibition on any experiment in any passive only band regardless of its impact on passive spectrum users. Having noticed this 2 days before the reconsideration filing deadline, it was not possible to convince the new client to both file and approve the drafting so as a public service we did it pro se and filed our own Petition for Reconsideration. We subsequently got supporting comments from both Boeing and Battelle Memorial Institute. No party opposed this issue.

The Commission apparently agreed with our logic stating

“As Marcus observes, Section 5.85(a) of the rules appendix in the R&O is inconsistent with both our existing treatment of conventional ERS licenses and the text of the R&O. This inconsistency arose in the NPRM, where the text proposed that only program licenses would be prohibited from using “restricted” bands (including passive service bands) listed in Section 15.205(a) of the Commission’s Rules. In contrast, Section 5.85(a) of the rules appendix proposed that all experimental use of “any frequency or frequency band exclusively allocated to the passive services” be prohibited. This inconsistency was not addressed by any commenting party, but the Commission’s stated intent in the text of the R&O was to continue previous practice regarding conventional ERS licenses.”

The new rules have the following reasonable safeguards to minimize unnecessary emissions in the passive bands:

§ 5.85 Frequencies and policy governing their assignment.

(a)(1) Stations operating in the Experimental Radio Service may be authorized to use any Federal or non-Federal frequency designated in the Table of Frequency Allocations set forth in part 2 of this chapter, provided that the need for the frequency requested is fully justified by the applicant. Stations authorized under Subparts E and F are subject to additional restrictions.

(2) Applications to use any frequency or frequency band exclusively allocated to the passive services (including the radio astronomy service) must include an explicit justification of why nearby bands that have non-passive allocations are not adequate for the experiment. Such applications must also state that the applicant acknowledges that long term or multiple location use of passive bands is not possible and that the applicant intends to transition any long-term use to a band with appropriate allocations.” (These last two sentences are a minor modification of our proposed wording on p. 14 of our Petition.)

When Docket 10-236 was initiated the Commission boldly stated

“The Federal Communications Commission today launched two proceedings that will help to promote investment and create jobs in developing innovative spectrum-efficient technologies and services to help meet the growing demand for wireless broadband services. The first action is a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking that seeks to expand the FCCÆs existing Experimental Radio Service rules to promote cutting-edge research and foster development of new wireless technologies, devices, and applications.”

Chairman Genachowski went on to state:

“With these two items, we build on our efforts to use spectrum more efficiently and in ways that deliver the highest value for the American people, and to encourage groundbreaking innovation….The goal is to accelerate innovation – to reduce the time for an idea to get from the lab to the market. A more extensive experimental licensing program would also help the FCC make smarter, faster decisions, by giving us on-the-ground intelligence on interference issues, and insight into the development of new cutting edge technologies. Encouraging research and development is vital to our objective of making the U.S. the spawning ground for the great technological advances of tomorrow. Past advances in technology, such as cellular networks and improvements in digital transmission techniques have led to vastly improved efficiency in spectrum use.”

While no one could disagree with these goals, this proceeding — like many other spectrum policy issues that are not the focus of large trade associations — is limping along on a very low priority and in the FCC as presently funded and operating that means things are getting done very slowly. Note that the revised rules in the R&O only went into effect 5 months after the adoption and release of the R&O, no doubt due to “back office problems” due to short staffing in the unglamorous parts of FCC where “there rubber hits the road”. Note also that while this docket adopted the new program license category for experiments, these are not yet available due to delays in getting funding within FCC to update the website for applications and then more back office problems with OMB approval of information requests.

Finally, note that this reconsideration under was related a little more than 2 years after the filing of reconsideration requests. This type of delay is typical for all spectrum items not related to incentive auction issues. (Note that the delays dealing with Docket 10-4 and the FM/LTE problem show that even the cellular industry can not get timely attention on non-incentive auction issues!) We note that some commissioners think there is currently too much delegated authority to FCC staff. Look at the new decisions and think about whether any of these issues needed or gained value from deliberations from 5 presidential appointees confirmed by the Senate?

In the coming months a major issue in this blog will be improving FCC spectrum policy productivity to keep up with the dynamic requirements of the spectrum-related industries and to help US competitiveness. We believe that productivity can be improved without new legislation, although new funding may be needed. (FCC costs are matched by user fees so new funding would not involve new tax dollars.)

UPDATE

Discussion of same decision from our friends at CommLawBlog.

FCC Congressional Spectrum Testimony & Millimeterwave Spectrum

Keeping the Pipeline Flowing

In the fall of 2014, the Commission unanimously initiated a proceeding to explore the feasibility of using bands above 24 GHz for mobile wireless broadband and other wireless applications.The Commission is taking a proactive approach to examine the future evolution of wireless broadband technologies and determine what steps to take to create a flexible regulatory environment in which these technologies can flourish.Conclusion

The Nation’s leadership in wireless, and our ability to meet the wireless needs of consumers, depends in large part on spectrum resources. We will continue to pursue effective spectrum policies, leveraging the tools Congress has provided. We will also look to this Subcommittee for assistance and guidance in developing new, innovative approaches to spectrum management, and standready to work with Congress and our federal partners towards these important goals.

We agree completely with the last paragraph. However, there previous paragraph raises serious questions about present FCC policy. While indeed FCC “unanimously initiated a proceeding to explore the feasibility of using bands above 24 GHz for mobile wireless broadband” in Docket 14-177, it has paid scant attention to other “spectrum frontier”issues before it and has tried to narrow the scope of Docket 14-177 to minimize its applicability to non-CMRS applications. See fn 64 of the NOI to see how the drafters were looking for excuses to do as little as possible in this proceeding. In that footnote, they reference the TAC report on Spectrum Frontiers saying “TAC suggested instead that the Commission should carefully balance the benefits and risks of adopting service rules in these bands and take an active role to establish a framework for coexistence with passive services.”

- So what is FCC now doing to “establish a framework for coexistence with passive services”?

- What about the bands above 24 GHz where there are no passive allocations at all? (e.g. 122.25-123 and 158.5-164 GHz)

- What about the bands above 24 GHz where the passive allocations are co-primary, not primary? (e.g. 102-109.5 GHz)

- What does FCC think that Sections 7(a) and 303(g) of the Communications Act actually mean?

Millimeter wave technology - It really is different

Why is FCC acting so slowly?

Fox News Rants on "War on Christmas" While FCC "War on Millimeter Waves" Continues

Today, in time for the holiday season, The Washington Post reports that Bill O’Reilly is back to his ranting on the “war on Christmas”. Something that is not obvious as holiday decorations are going up everywhere and holiday music is becoming ubiquitous.

But also today I got from a client an FCC rejection of a millimeter wave experimental application that had the attached explanation:

“You are advised that the Commission is unable to grant your application for the facilities requested. We have received an objection to your application from NSF. If you still wish to pursue this testing, you should exclude the passive band (X - Y) GHz on your application to further discuss your request prior to refilling.” (We are not giving the exact band here to protect the privacy of the applicant)”

This action is a natural consequence of the bizarre revision of § 5.85(a) in the Report and Order of Docket 10-236 on January 31, 2013 that apparently was a clerical error! A timely Petition for Reconsideration as filed by your blogger and received support from several parties, including Boeing - a real Fortune 500 corporation with a real lawyer representing them! Since then - NOTHING! Except of course, today’s rejection of the client’s application. (Your blogger was not involved in the filing, so this rejection is actually income generating, so thanks FCC in a way!)

The § 5.85(a) problem is only one part of the FCC’s 3 prong “war on millimeterwaves”. As described here previously, the other 2 prongs are:

- The inaction on the 7/1/13 IEEE-USA petition seeking to to declare technology above 95 GHz to be presumptively “new technology” in the context of 47 USC 157 and therefore entitled to timely consideration with the burden of proof on those opposed to such new technology

- The failure of the RF safety NPRM, Docket 13-84, to propose quantitative safety standards above 100 GHz even though it is based on an IEEE standard that goes to 300 GHz.

While one might argue that the NOI in Docket 14-177 is a major change in the “war on millimeter waves”, a careful reading shows that the authors tried very hard to limit the coverage to both 24-86 GHz only as well as to mobile only, although there is passing mention of cellular backhaul.

So while the “war on Christmas” exists only in the minds of a few people at Fox News, the “war on millimeter waves is quite real at FCC!

New Millimeter Wave Textbook Just in Time for 24+ GHz NOI

In some ways this book is reminiscent of the pioneering 1976 publication of Robert Dixon’s Spread Spectrum Systems with Commercial Applications. At the time Dixon’s book was published there were published articles on most aspects of spread spectrum/CDMA technology, but they were scattered other a lot of different journals, often with different jargon, nomenclatures, and symbology in equations. While Dixon had few equations, he tied all the concepts together in a single approachable book. Similarly, but at a higher technical level, this book ties together its subject matter in a consistent way from a variety of sources, although in this case the authors are themselves major pioneers themselves in this technology.

The title’s, Millimeter Wave Wireless Communications, use of the term “wireless” needs a little clarification. It is used primarily in the context of its use in “CTIA-The Wireless Association” - to mean what we spectrum policy wonks call CMRS - commercial mobile radio systems. More specifically it deals with base station/mobile uplinks and downlinks in the mmW region - something that was thought inconceivable a decade ago. However, it also deals with unlicensed 60 GHz systems such as those permitted under §15.255. It does not deal with fixed services such as the 70, 80, and 90 GHz systems authorized under §101.1501+ and does not deal with other radio services such as satellite systems, except in brief parenthetical sections. But within its scope it is very thorough and unique in its comprehensive treatment of this rapidly evolving technology. I would urge the authors to expand the scope to include fixed systems in the almost certain next edition since much of the present material already applies to both mobile and fixed.

Since this is a spectrum policy blog, let us mentioned a final concern: the discussion of the evolution of US mmW regulations has some minor garbles. For example on p. 507 it states that in 1998 “USA became the first country in the world to authorize low power unlicensed 60 GHz operations”, while 2 pages later it says “In 1995, the FCC allocated the 57-64 GHz frequency band for unlicensed communications” - which is the correct date although the initial band was 59-64 GHz. Readers wanting a more detailed and accurate history, including the key 1988 study from the UK spectrum regulator suggesting unlicensed in 60 GHz, might wish to read your blogger’s history page on the subject. However, most readers of the book will not be spectrum policy wonks and will probably glance over these details.

But the people who have to draft comments in Docket 14-177 and those who will be designing mmW mobile systems needs not be concerned about these points. Within its prime subject matter of CMRS uplinks/downlinks it ties together for the first time information in disparate issues such as

- multipath mobile mmW propagation,

- atmospheric effects

- antenna technology including adaptive antenna technology to overcome the multipath,

- mmW device technology, and

- high level design issues

866 Mbps Achieved in Unlicensed 60 GHz Band

.Samsung Electronics announced the development of its 60GHz Wi-Fi technology that enables data transmission speeds of up to 4.6Gbps, or 575MB per second, a five-fold increase from 866Mbps, or 108MB per second, the maximum speed possible with existing consumer electronics devices. As a result, a 1GB movie will take less than three seconds to transfer between devices, while uncompressed high-definition videos can easily be streamed from mobile devices to TVs in real-time without any delay.

“Samsung has successfully overcome the barriers to the commercialization of 60GHz millimeter-wave band Wi-Fi technology, and looks forward to commercializing this breakthrough technology,” said Kim Chang Yong, Head of DMC R&D Center of Samsung Electronics. “New and innovative changes await Samsung’s next-generation devices, while new possibilities have been opened up for the future development of Wi-Fi technology.”

Unlike the existing 2.4GHz and 5GHz Wi-Fi technologies, Samsung’s 802.11ad standard 60GHz Wi-Fi technology maintains maximum speed by eliminating co-channel interference, regardless of the number of devices using the same network. By doing so, Samsung’s new technology removes the gap between theoretical and actual speeds, and exhibits actual speed that is more than 10 times faster than that of 2.4GHz and 5GHz Wi-Fi technologies.

Until now, there have been significant challenges in commercially adopting 60GHz Wi-Fi technology , as millimeter waves that travel by line-of-sight has weak penetration properties and is susceptible to path loss, resulting in poor signal and data performance. By leveraging millimeter-wave circuit design and high performance modem technologies and by developing wide-coverage beam-forming antenna, Samsung was able to successfully achieve the highest quality, commercially viable 60GHz Wi-Fi technology.

In addition, Samsung also enhanced the overall signal quality by developing the world’s first micro beam-forming control technology that optimizes the communications module in less than 1/3,000 seconds, in case of any changes in the communications environment. The company also developed the world’s first method that allows multiple devices to connect simultaneously to a network.

As is the case with the 2.4GHz and 5GHz spectrum, the 60GHz is an unlicensed band spectrum across the world, and commercialization is expected as early as next year. Samsung plans to apply this new technology to a wide range of products, including audio visual and medical devices, as well as telecommunications equipment. The technology will also be integral to developments relevant to the Samsung Smart Home and other initiatives related to the Internet of Things

Note the first sentence of the last paragraph: “As is the case with the 2.4GHz and 5GHz spectrum, the 60GHz is an unlicensed band spectrum across the world”. This did not happen by accident. It happened because of FCC initiatives in the 1980s and 90s that recognized technological advances had made new technology possible that was prohibited by anachronistic FCC rules at those times. The initiatives removed those prohibitions but did not require incumbent users to change their operations on bit nor did it increase their interference risk. As a result we have had technical innovation and economic economic growth.

While other WiGig companies like Intel, Wilocity (now owned by Qualcomm) and Nitero have been developing super-fast radios that work 60GHz channel, Samsung claims they’ve actually produced these enhanced speeds by fixing interference issues caused by other devices on the channel.

Now the problem is that the new NOI is rumored to contain a discussion about possible partial or total repurposing of the 60 GHz band for cellular communications, presumably on a licensed basis. The question to be considered on the 8th Floor is how will the fording of the 60 GHz discussion impact capital formation for innovative unlicensed 60 GHz technologies. We are sure the 60 GHz companies have less visibility on the 8th Floor than the major CTIA members and their insatiable demand for spectrum.

We hope the 8th Floor considers carefully the wording of such discussion and its impact on capital formation for ongoing unlicensed 60 GHz systems.

Chmn. Wheeler, Tear Down This 95 GHz Wall!

On October 17, FCC will consider a millimeter wave (mmW) NOI that will be the first major mmW deliberation there in more than a decade. mmW is sometimes called the “spectrum frontier” and is the upper end of radio spectrum that is enabled by breakthrough technology. Indeed, a major motivation for the NOI is that the work of Ted Rappaport of NYU and others has shown that mobile use above 24 GHz is practical.

(Your blogger recalls that in the early 1980s when Motorola was pushing for more Part 90 sharing of UHF TV spectrum - an action that indirectly resulted in DTV due to an NAB backlash - Motorola and others claimed land mobile above 1 GHz was physically impossible!)

Description of 10/17 NOI from FCC Tentative Agenda

Due to military R&D, US firms are the leaders in basic mmW technology, but commercial mmW applications lag in part due to outdated FCC policies and the general procedure of FCC to wait for petitions its in inbox. Does FCC really think that it is easy to raise capital for moving technology from IEEE journals to the marketplace win part of the process is getting FCC to act on a rulemaking to permit the new technology? As part of my teaching last year, I asked 3 prominent communications attorneys in DC how long they thought it would take for FCC to act on approving a new technology using the verging spectrum above 95 GHz. The answers were all in the 3-5 year range!

This is not how we facilitate US technological competitiveness and economic growth. The roots of Wi-Fi and Bluetooth was a policy of FCC Chairman Ferris, later supported by Chairman Fowler, that FCC should identify promising technologies held back by anachronistic FCC policies and modify those policies to allow the technologies - with due deference to others who might be adversely affected - but not to require the new technologies. Indeed, Qualcomm cofounder Andrew Viterbi has said that the May 1985 FCC spread spectrum decision was important in enabling the final capital formation for the incorporation of Qualcomm 3 months later as it showed real FCC interest in CDMA which was then opposed by most mainstream industry players. (Cofounder Irwin Jacobs and the current Qualcomm management differ on this point and some others about the early company history.)

Now FCC has an analogous wall in spectrum policy at 95 GHz, depicted at the top of this post. While FCC (and ITU) has spectrum allocation up to 275 GHz, it has no unlicensed or licensed service rules above 95 GHz, a point reached in October 2003. At left is a Japanese 125 GHz system used at the 2008 Beijing Olympics in quantity for moving view from stadiums to the broadcast center. Use of similar technology is not permitted under current FCC Rules! So is it surprising that despite US leadership in millimeter wave components no such systems are being made in USA?

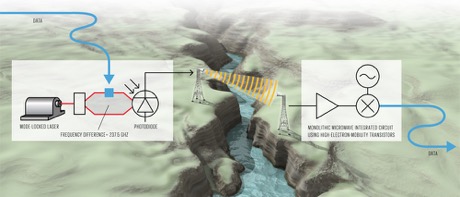

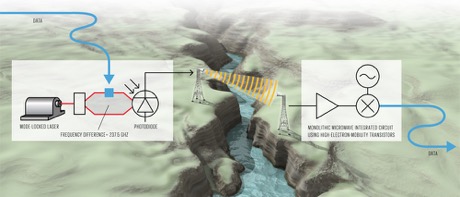

Above is a diagram of a German 237 GHz System exceeding 100 Gbits/s. Not only is its sale and use illegal in USA, but such an experiment probably could not have even been authorized due to the recent glitch in §5.85(a) that came about in the Report and Order of Docket 10-236 that for the first time forbids all experiments in passive bands. This change was made without any explanation and without any supporting comments. A timely filed Petition for Reconsideration on this issue has received no objections in more than a year and is supported by others, yet the matter is still unresolved at FCC. (Note, if FCC can not complete the whole reconsideration order on this docket in a timely way, it could at least issue a public notice announcing an interim liberal waiver policy for mmW experiments that impinge on passive bands based on whether there will actually be interference at the place and time of the experiment and NTIA - home of “spectrum sharing is the new normal” - could say that it supports such a policy as all such bands are G/NG shared.)

So here is what we urge FCC to do at the 10/17 meeting:

- Make clear in the NOI that the wall at 95 GHz is not intentional and is not a fundamental barrier to any proposed mmW uses.

- Make clear that despite theTentative Agenda description given above for the NOI that FCC is open to consider all uses of spectrum in the mmW bands, fixed, mobile and others and promises timely consideration of new proposals in order to support US competitiveness in mmW technology

"Aux Armes" Netoyens:

End the War on Millimeter Wave Technology

The chorus of the Marseillaise, the French national anthem begins with:

Which translate toAux armes, citoyens,

Formez vos bataillons,

Marchons, marchons !

To arms, citizens,

Form your battalions,

Let's march, let's march!

(While I lived in Paris, I often walked by Eugène Delacroix’s masterpiece Liberty Leading the People [La Liberté guidant le peuple] while visiting the Louvre. [Oddly, the painting also made a rare overseas trip to Tokyo in 1999 when I was living there and was the hit of the town during its visit.] The words of the Marseillaise and the picture describe events and the initial idealism of the French Revolution. But while the”armes”/“arms” in the above lyrics means weapons, what is needed in the context of this post is the use of human arms to write to FCC and advocate constructive action.)

The commentators of Fox News repeatedly comment on the “war on coal” and the “war on religion”. Well, the “war on millimeter (mmW) wave technology” at FCC is just as real and easier to document, although it is no doubt unintentional. There are 3 proceedings at FCC that document FCC’s present disinterest/apathy towards commercial use of cutting edge microwave technology, even as our national competitors advance in this area.

While not exactly an issue comparable to the causes of the French Revolution, the current situation of US regulation >95 GHz needs the urgent attention of “netoyens”, especially researchers and firms dealing with millimeter wave technology. While the FCC Rules have spectrum allocations up to 275 GHz, the lack of “service rules” beyond 95 GHz (with the minor exception of certain amateur radio and ISM bands) makes regular commercial licensed or unlicensed mmW use impossible. This in turn greatly complicates capital formation for such technology because VCs can easily find other technology to invest in that does not involve making a prominent FCBA member a member of your family for several years and paying his children’s college tuition while at the same time the entrepreneur has no access to market and bleeds red ink.

Sadly, with the exception of the IEEE 802 LAN/MAN Standards Committee (the techies behind Wi-Fi standards), Boeing, and the more obscure (at least in FCC circles) Battelle Memorial Institute and the rather obscure Radio Physics Solutions, Inc., no commercial interests have filed comments with FCC on 3 key issues blocking capital formation for technology above 95 GHz and by extension hindering US competitiveness in advanced radio technology.

The 3 dockets involved are:

- Docket 10-236 which as previously reported here was supposed to encourage experimentation had the apparently unintended effect of complicating millimeter waver research by forbidding, for the first time and without an explanation, all experimental licenses in bands with only passive allocations independent of whether there was any impact. Many mmW bands have only passive allocations and it is difficult a and expensive to avoid them in initial experiments with new technology and it is not important if there is no passive use near the experiment than could get interference. Since the text of the Report and Order contradicts itself on this issue, the simplest explanation is that a sentence was put in the wrong section. Your blogger filed a timely reconsideration petition when he noticed this 2 days before the deadline and that had been supported by Battelle and Boeing and has been opposed by none. But FCC doesn’t necessarily react in a timely way, specially when incentive auctions are very distracting and staffing is low, unless there are multiple expressions of concerns, preferably from corporate America.

- Docket 13-259 deals with the IEEE-USA petition seeking timely treatment of new technology proposals for this green field spectrum >95 GHz under the terms of 47 USC 157, although any clear statement from FCC on how to get timely decisions on such spectrum would be useful.

- Docket 13-84 has proposed updating the Commission’s RF safety rules. The rules currently only have numeric limits up to 100 GHz - the upper limit of the standard they were based on when they were last updated almost 2 decade ago - but the new proposals are silent on numeric limits above 100 GHz even though the standard that is now the base of the regulations now goes to 300 GHz! This lack of a specific safety standard above 100 GHz adds even more to the regulatory uncertainty of those interested in mmW technology. With today’s mmW technology, the specific numeric standard doesn’t really matter much because exposures will be low. But this proposal to leave ambiguity for mmW systems can be very damaging. Battelle has proposed one way to deal with a specific standard. Others interested in mmW technology should either support it or propose an alternative.

So netoyens, Aux armes! The time has come to take your arms (and the attached hands) and write to FCC urging timely action on these three dockets to level the playing field for mmW technology and help US competitiveness.

As a public service, Marcus Spectrum Solutions LLC will draft comments in these 3 dockets for any US manufacturer of mmW equipment dealing with the issues above at no charge to reflect whatever your viewpoints are.

(Note MSS is not licensed to practice law so this offer does not involve the practice of law. Let’s discuss what your viewpoints are and we will draft a document for review by your legal staff.)

Japanese 120 GHz system used at 2008 Beijing Olympics

German 237 GHz System exceeding 100 Gbits/s

( An experiment probably not permitted under the terms of the recently revised §5.85(a))

Chrysler Superbowl Ad on “American Pride” - MSS believes that advanced wireless technology is just as American as automobile production in Detroit. US can compete if FCC doesn’t slow innovation!

Free the Spectrum >95 GHz!

Your blogger’s comments on Docket 13-259, the IEEE-USA petition to FCC asking that technology greater than 95 GHz be declared “new technology” subject to timely consideration under Section 7 of the Communications Act are now posted on the FCC site. As of this writing, also posted as early filings are comments from IEEE 802 and from David Britz, a former research in the area for AT&T.

If you are interested in facilitating the introduction of commercial technology above 95 GHz, presently forbidden by law in the US and facing multiyear case-by-case deliberations, you may wish to consider telling FCC whether you agree with the points made in the above comments. Feel free to disagree on issues. Heck, feel free to say that use of spectrum above 95 GHz is not even in the “public interest” -- if that is what you believe.

Note to those interested in passive uses such as radio astronomy and remote sensing: bands for such uses are already allocated and protected and are not under consideration here for nonpassive use. The issue here is actual access to bands that already have fixed and mobile allocations but have no FCC service rules.

FCC Requests Comment on IEEE-USA >95 GHz Petition

In a Halloween present to your blogger, FCC released the above PN asking for comment on the previously discussed IEEE-USA petition to expedite deliberations on technology >95 GHz in accordance with the terms of Section 7 of the Communications Act.

In an apparent clerical error they omitted either an RM number or a Docket number creating an ambiguity on how to actually file comments. A knowledgeable source says this happens sometimes and is normally corrected in a day or 2.

We look forward to seeing your comments.

vox populi, vox dei

UPDATE

FCC issued an erratum on November 1 and now this issue is docketed as ET Doc. 13-259.

By my calculation, comments are due December 2, 2013.

For those who do not do this often, the link for uploading a comment into this docket is at

http://apps.fcc.gov/ecfs/upload/display?z=e83p0

Convert your comments to .pdf format before uploading to FCC

.

Remember to enter 13-259 in the first entry block labeled

“Proceeding Number: ![]() ”

”

If you need any help, place contact your blogger

Where Does The Radio Spectrum End?

The article start off with

At the upper end of the spectrum ITU gives 3000 GHz or 3 THz as the upper limit of its jurisdiction. This is the region of infrared which is normally described by wave-length not the equivalent frequency, so for reference 3 THz is equivalent to 100 μm. While ITU gives a numeric limit for the upper limit of radio spectrum, there is some disagreement in the infrared/optics community of the lower limit of infrared technology with various sources giving numbers in the range of 1–3 THz.

For many purposes the difference between RF and infrared is the type of technology used and there is a growing convergence as many recognize that there is a transition zone where technology from both disciplines can be used together. Thus RF technology has be classically characterized by components such as mixers and antennas and infrared technology by lenses and diffraction gratings and new innovative systems use components from both traditions.

The full text of the article is available to SpectrumTalk readers here.

TAC on Spectrum Frontiers: Where Does Innovation Come From?

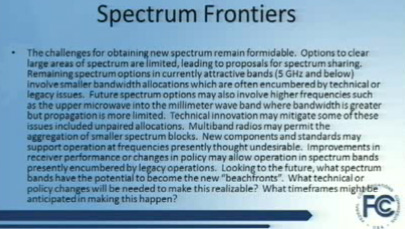

Visual from 3/11/13 FCC TAC meeting

On Mach 11, 2013 the FCC’s Technology Advisory Council held its first meeting of the year. In stark contrast to previous FCC chairmen, Chairman Genachowski opened the meeting and seemed to enjoy being with this group. (I recall when the Disney CTO resigned from TAC a decade or so ago because of his perception that there was no interest in its advice from the 8th Floor and his observation that in a parallel group at SEC that agency’s chairman regularly met with the advisory committee.)

Part of the deliberations dealt with “Spectrum Frontiers” and the slide projected for that discussion is shown at the top of this post. It correctly says that future systems may move into the millimeter wave (mmW) band (frequencies above 60 GHz) and that technical innovations may make use of such higher frequencies more practical.

If you were to ask a prominent communications attorney to do due diligence on a business plan involving technology above 95 GHz I suspect he would report back to potential investors that there would be a 3-4 year delay for new service rules based on recent FCC performance in Title III regulation - think UWB, BPL, AWS-3, TVWhitespace, LightSquared, etc. Would anyone in their right mind invest in technology subject to such regulatory uncertainty?

FCC Chairman Charles Ferris (1977-81)

In order to get the investment needed for practical technology in these bands, FCC must give assurance to developers and investors that any deliberations will be both transparent and timely. Comm. Pai has rediscovered the long lost Section 7 of the Communications Act. (It wasn’t really lost, just ignored by FCC for almost 30 years on a bipartisan basis.) Rather than have the TAC deliberate on how this now idle spectrum might be used - perhaps with Soviet-style planning, let’s have faith in the marketplace and encourage capital formation for technology development >95 GHz by giving assurances of timely consideration of any new service rules.

Why doesn’t FCC just declare that technology >95 GHz is presumed to be “new technologies and services to the public” and thus subject to the terms of Section 7. As I read Section 7(a) it would apply to both FCC and NTIA - important since all bands >95 GHz are shared and thus subject to NTIA coordination. (Section 7(b) clearly only applies to FCC.)

Frequencies Above 95 GHz: Why Not Declare that Section 7 Presumably Applies in Order to Stimulate US Innovation and Economic Growth?

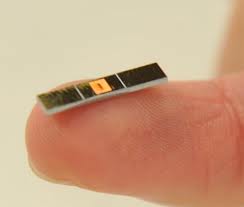

135 GHz antenna developed by Singapore

government lab and announced last week

(The fact that this antenna looks so unusual is an

indication that technology at this band is very

different and conventional regulatory thinking

may be inappropriate.)

Almost on cue from my 8/25/22 post on moving the upper limit of FCC radio service rules above 95 GHz, RF Globalnet published on 8/28/12 a post entitled “A*STAR's IME Develops Smallest Antenna That Can Increase WiFi Speed By 200 Times”. A*STAR is the Singapore Agency for Science, Technology and Research, the “lead agency for fostering world-class scientific research and talent for a vibrant knowledge-based and innovation-driven Singapore” - somewhat of a combination of the US’ NSF and national laboratories (e.g. Argonne National Lab) in a state capitalism industry model. (Original A*STAR press release)

The RF Globalnet article reported (in Singapore/Commonwealth spelling):

Researchers from A*STAR’s Institute of Microelectronics (IME) have developed the first compact high performance silicon-based cavity-backed slot (CBS) antenna that operates at 135 GHz. The antenna demonstrated 30 times stronger signal transmission over on-chip antennas at 135 GHz. At just 1.6mm x 1.2mm, approximately the size of a sesame seed, it is the smallest silicon-based CBS antenna reported to date for ready integration with active circuits. IME’s innovation will help realise a wireless communication system with very small form factor and almost two-thirds cheaper than a conventional CBS antenna. The antenna, in combination with other millimetre-wave building blocks, can support wireless speed of 20 Gbps – more than 200 times faster than present day Wi-Fi, to allow ultra fast point-to-point access to rich media content, relevant to online learning and entertainment.

So the Japanese have a product prototype at 120 GHz that they used at the Olympics 4 years ago and a Singapore government lab is developing 135 GHz commercial technology. Where do US firms stand? There is some interest among US firms in this area. The US-based IWPC MoGig group includes several US entities such as AT&T and Northrop Grumman. But a rational “due diligence” assessment of regulatory risk by anyone wanting to invest in R&D in these bands would lead to great regulatory uncertainties at present:

- Only experiment licenses are possible with no guarantee of renewal or expectation of protection

- Unlicensed use is impossible

- The legality of equipment sales is questionable

- The time for FCC to respond to a waiver request or a petition for rulemaking to permit a specific product to be sold and used in these bands is in the multiyear range and the need for NTIA coordination (all these bands are G/NG shared) is complicated since there is no public information on federal government uses or requirements in these bands other than radio astronomy and passive sensing

Recall the words of Comm. Pai in his maiden speech at CMU in July:

I’ve met with those in the private sector who decide whether to make investments and to create jobs and have asked what’s holding them back. The principal answer that I have received has been remarkably consistent, and it can be summed up in two words: “regulatory uncertainty.”

Some of the factors that contribute to this uncertainty fall outside of the FCC’s jurisdiction, such as taxes, health care, and financial regulation. But concerns are expressed regarding the FCC in two general ways. The first involves inaction, or delayed action, by the Commission. At first blush, it may seem odd for those in the private sector to be complaining that its regulator is moving too slowly. Entrepreneurs are usually happy to be left alone, free to innovate without government intervention.

But the communications industry often doesn’t fit that stereotype given the FCC’s pervasive role. If a company wants to market a new mobile device, it needs the FCC’s approval. If a company wants to purchase another firm’s spectrum licenses, it needs the FCC’s approval. If a company wants to provide a new wireless service, it needs the FCC’s approval. And if a company finds that there isn’t any spectrum available and proposes the reallocation of inefficiently used spectrum, it needs the FCC’s approval.

In the same CMU speech Comm. Pai rediscovered Section 7 of the Communications Act. I say “rediscovered” because FCC has been consistently ignoring it under both Republican and Democratic administrations since it was passed in 1983. (While I have wondered if Section 7 was redacted from all copies of the Comm Act at FCC, an 8th Floor insider has assured me recently that it isn’t, and it is not censured from the online version of WestLaw at FCC either.)

Comm. Pai has the same understanding of Section 7 that I have:

“Looking at that provision, the message from Congress is clear: The Commission should make the deployment of new technologies and new services a priority, resolving any concerns about them within a year.”

It is interesting to read Section 7(a) (47 USC 157(a)) in the light of the FCC/NTIA Section 301/305 dichotomy and in view of the fact that any action in these shared bands de facto requires NTIA concurrence. Without the benefit of any formal legal education, let me state that the policy provisions of Section 7(a) applies to both FCC and NTIA. Further, the requirement that

Any person or party (other than the Commission) who opposes a new technology or service proposed to be permitted under this chapter shall have the burden to demonstrate that such proposal is inconsistent with the public interest.

would indicate that NTIA (and IRAC) is a “person or party other than the Commission” and thus has “burden to demonstrate that such proposal is inconsistent with the public interest”.

But here is a humble suggestion: