FCC Starts Jammer Enforcement on a Large Scale

Readers may recall that enforcement has been a recurring theme here and your blogger has criticized both the Commission for its disinterest and major trade associations that have myopically made this a low priority issue in their interactions with FCC.

The PN stated,

The FCC Enforcement Bureau has issued 20 enforcement actions against online retailers in 12 states for illegally marketing more than 200 uniquely-described models of cell phone jammers, GPS jammers, Wi-Fi jammers, and similar signal jamming devices. These devices have the capacity to prevent, block, or otherwise interfere with authorized radio communications in violation of section 302(b) of the Communications Act and sections 2.803 and 15.201(b) of the Commission’s rules.

The Enforcement Bureau’s actions are intended to warn retailers and potential purchasers that marketing, selling, or using signal jamming devices in the U.S. is illegal and that the FCC will vigorously prosecute these violations.

Enforcement Bureau Chief Michele Ellison said, “Our actions should send a strong message to retailers of signal jamming devices that we will not tolerate continued violations of federal law. Jamming devices pose significant risks to public safety and can have unintended and sometimes dangerous consequences for consumers and first responders.”

Unfortunately EB included in the Citation text that clearly would have gotten a staffer into trouble during my nearly 25 year tenure at FCC: it prejudged the commissioners on something they had never ruled on. Para. 9 of the Citation states

Signal jammers, however, cannot be certified or authorized because their primary purpose is to block or interfere with authorized radio communications. As noted above, a device intended for such use is clearly prohibited by section 333 of the Communications Act. Thus, signal jammers such as those offered by each of the Online Vendors identified in Appendix A cannot comply with the FCC’s technical standards and therefore cannot be marketed lawfully in the United States or its territories.

First, “ a device intended for such use is clearly prohibited by section 333 of the Communications Act” is clearly not the meaning of Section 333 which deals with jamming, not jamming equipment. Section 302(b) gives the Commission to ban equipment that does not complies with its regulations for transmitters and the lack, at present, of any such regulations for jammers is thus illegal. Isn’t that clearer than misconstructing Section 333? I believe that anyone with a legal background will see that the references to Section 333 in the Citation adds nothing to this marketing case and is only posturing unsupported by any citations to regulation or precedent.

In its new found jammer marketing enforcement enthusiasm, EB also updated its FAQ on GPS, Wi-Fi, and Cell Phone Jammers. Unfortunately, in doing so it pandered excessively to CTIA lobbying and ignored the lack of any en banc Commission precedent on its interpretation of Section 333. The new FAQ, gives the text of Section 333 and then states “Jammers cannot be marketed or operated in the United States except in the very limited context of authorized, official use by the federal government.” This, at best, fuzzifies whether the Commission has the legal jurisdiction to authorize jammers in some contexts for nonfederal users and fully agrees with CTIA petition of November 2, 2007 that the Commission has never even asked for public comment on (with the exception of the section on bidirectional amplifiers that is being considered in Docket 10-4).

This highlights the inability or unwillingness of the Commission to take any action on the CTIA petition or to take any action on contrary points of view in the July/August 2009 petition of the South Carolina Department of Corrections and 30 other states to allow jamming in prisons to control illicit cellphone use and the 7/20/11 GTL petition that deals with both jamming and “managed access”. Both of the latter petitions contain legal arguments addressing why Section 333 does not limit the Commission’s jurisdiction in this area. So if this were so clearcut, FCC would have dismissed the CTIA petition as moot and the other petitions as being beyonds its jurisdiction. However, the 8th Floor remains silent on this public safety issue apparently for fear of offending CTIA.

So kudos to EB for the enforcement action it has initiated at last and a minor criticism for its pandering to CTIA on the FAQ. Let’s hope that EB follows through on this enforcement action by working with DOJ to seize inventory and assets of the perpetrators, not just asking them to reply and giving them opportunity to restructure. EB’s predecessor, the former Field Operations Bureau used to take such aggressive action from time to time. A few veterans of that era still work in EB, maybe they should be consulted on more assertive options for these devices that endanger public safety.

But at the risk of sounding like a broken record, isn’t it time for FCC to address the several petitions it has on prison jamming where the intention is to protect the public safety and resolve both the jurisdictional issue Section 333 and the technical issue of whether the benefit of prison jamming outweighs whatever interference risk it determines results from it?

UPDATE (11/13/11)

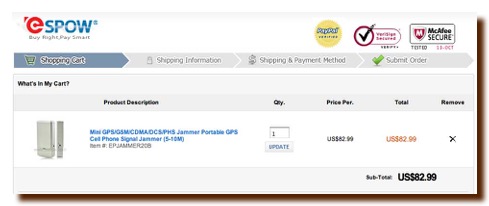

As your blogger expected, the EB action above did not get immediate compliance. Today, at least one of the cited firms, Espow International, Ltd of Jersey City, NJ (http://www.espow.com/) was still selling the very models cited!

Those of us with experience in the former FOB know that this type of citation is not reliable in achieving compliance for people profiting from such obviously illegal equipment. FOB used to get court orders to seize inventories of personal computers that did not have proper FCC equipment authorization and that posed much less of a public safety threat than the unauthorized jammers involved here.

The equipment importing and marketing sectors know full well that for the past decade or so FCC has shown little interest in marketing enforcement and bolder action is needed to overcome a decade of inaction. Generally, such enforcement at FCC has no constituency and projects without strong outside supporter tend to get few resources at FCC. The major trade groups will have to unite and praise FCC for these first steps but urge more assertive action to start a real cleanup.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](valid-rss-rogers.png)